On 18 July 1290, a cataclysmic event took place that was to have far-reaching consequences. King Edward I ordered the expulsion of the Jews from England. Only in 1657, a total of 367 years later, were the Jews permitted to return to England. The Edict of Expulsion has usually been interpreted as the inevitable culmination of worsening persecution against the Jews.

By 1290, the Jews were an accepted presence in English society, although Christians viewed them with ambivalence. Economically, Jews could enjoy great influence. Loans with interest were permitted between Jews and non-Jews, contrary to English practice which expressly forbade usury, which was regarded by the Church as a heinous sin. While Jews could benefit from lending money at high rates of interest, they were also vulnerable to the whims of the king, who could levy heavy taxes on them without summoning Parliament. Their reputation as extortionate moneylenders, whether deserved or not, could make them unpopular among their Christian fellows.

In wider society, as W.D. Rubinstein has noted, anti-Jewish attitudes were prevalent. These stemmed from, and were encouraged by, negative images of the Jew as a diabolical figure that preyed on innocent Christian children. Jews were vulnerable to accusations of ritual murders; most notably, William of Norwich (d. 1144) and Little St. Hugh of Lincoln (d. 1255). Walter Laqueur opined that: 'There have been about 150 recorded cases of blood libel... that resulted in the arrest and killing of Jews throughout history, most of them in the Middle Ages. In almost every case, Jews were murdered, sometimes by a mob, sometimes following torture and a trial'.

Above: William of Norwich (left) and Little St. Hugh of Lincoln (right).

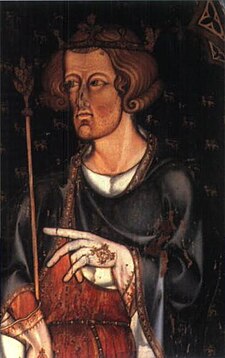

Hostility to the Jews occasionally erupted in violence and bloodshed. Massacres occurred in 1189 and 1190; in York, over 100 Jews were massacred while hiding in a tower. The situation gradually worsened as, less than thirty years later, in 1218, Jews were required to wear a marking badge. Over the course of the thirteenth-century, Jews were heavily taxed. In 1275, King Edward I issued a statute that placed a number of restrictions on the Jews in England, in which he outlawed the practice of usury. Later, the king charged the Jews with failing to follow the Statute of Jewry, and he ordered their expulsion from the country in July 1290.

Only in the seventeenth-century were Jews officially permitted to return to England. The widely anti-Semitic attitudes that characterised medieval and early modern Europe, as a whole, did not disappear in modern times. The Holocaust, which claimed the lives of roughly 6 million Jews, built on and was encouraged by anti-Jewish propaganda that had existed on the Continent for hundreds of years.