In 1437, a week ago today, Queen Joan of Navarre died in London at the age of about sixty-six. Joan is one of the lesser known medieval queens of England and her controversial reputation is founded on the accusations of witchcraft that were levied against her by her stepson, Henry V. This neglect of Joan is unfortunate, because in reality she was one of the most intelligent, politically astute and capable consorts. Recently, I undertook research into Joan's life and discovered that there was a great deal more to her story than the rumours of sorcery that blackened her name.

Born around 1370 in Pamplona, Navarre, Joan married her first husband while still a teenager, in 1386. Her husband was John IV, duke of Brittany. The marriage appears to have been successful and the couple had nine children together. As duchess of Brittany, Joan participated in the ceremonies of court and she is known to have interceded for individuals who displeased her mercurial husband, including Clisson, constable of France. In her activities, Joan conformed entirely to contemporary expectations of how a noblewoman should behave. She fulfilled the roles of mother, wife, intercessor and patron. Her interest in court ceremonial, moreover, indicates that she was both cultured and artistic.

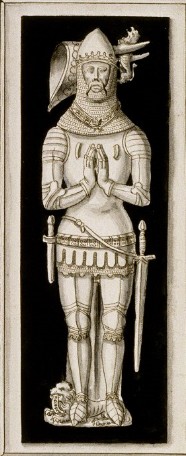

Above left: John IV, duke of Brittany, Joan's first husband.

Above right: Henry IV of England, Joan's second husband.

In 1399, when Joan was around the age of twenty-nine, her husband died. She chose not to remarry immediately after her husband's death and instead fulfilled the role of regent for her son, John V, during his minority. It was during this period that Joan clearly emerges as a politically astute, capable and wise ruler. In 1403, she remarried. Her second husband was Henry IV of England. By marrying Henry, Joan placed herself in an ambiguous position, for her husband was a usurper. As with the later consorts Elizabeth Wydeville and Anne Neville, whose husbands also unlawfully usurped the throne, Joan was required to legitimise her husband's claim to the throne. Rumours circulated that there had been long-standing affection between Henry and Joan, and it is possible that their marriage was a love match.

However, Henry also demonstrated shrewdness in selecting Joan to be his consort. She was highly experienced in the affairs of government, intelligent and pragmatic. Moreover, in bearing her first husband nine children, she was clearly fertile, which was undoubtedly important for a medieval king whose claim to the throne was not fully secure. Unfortunately, during their ten-year marriage Joan did not bear Henry an heir, although it is possible that she experienced stillbirths. Fortunately, the queen enjoyed excellent relations with her stepchildren, including her husband's son Henry.

Above: Henry V, Joan's stepson.

Henry IV's death, however, changed Joan's life. Financially straitened, the new king, Henry V, accused Joan of witchcraft in a ruthless attempt to seize her lands and income with which to finance his foreign wars. As a highborn woman, Joan was vulnerable to accusations that were usually gender specific: namely witchcraft, sorcery and adultery. Other medieval noblewomen suffered from similarly ignominious accusations: both Eleanor Cobham, duchess of Gloucester, and Jacquetta, duchess of Bedford, were accused of witchcraft. There is no surviving evidence that Joan ever engaged in activities associated with witchcraft, and it is surely significant that she was later restored to favour.

During her imprisonment, Joan resided at Pevensey Castle and later at Nottingham Castle. Her stepson died in 1422 and was succeeded by his only son, Henry VI. Joan died on 10 June 1437, the same year in which her successor, Katherine of Valois, also died. As with many medieval queens, there is a lack of evidence concerning Joan's life and her experiences as queen. However, she seems to have enjoyed success during her husband's reign, but his death placed her in an ambiguous position, for she had borne him no children and thus was unable to exert influence in the politics of her stepson's reign. With no-one to support her interests, she was vulnerable to the whims of Henry V and was humiliated when he seized her income to finance his wars on the Continent. Although she died in obscurity, Joan of Navarre emerges as a politically astute, intelligent and influential consort, whose eventual fate bears witness to the dangers faced by highborn women in the Middle Ages.