Above: Portrait of a Lady, perhaps Katherine Howard; Royal Collection Trust

A portrait miniature in the Royal Collection Trust, dating to circa 1540, has for some time been identified as a likeness of Katherine Howard, fifth queen consort of Henry VIII, who was beheaded in 1542. There are two versions of the miniature; the second version is held in the Buccleuch Collection, and was originally owned by Thomas Howard, earl of Arundel. The sitter has customarily been identified as Queen Katherine based on her jewellery; the necklace, in particular, appears to be the same as that worn by Jane Seymour, the king's third wife, in the portrait created of her in 1536-7 (see below).

Above: Portrait miniature of Katherine Howard (?), Buccleuch Collection

The item of jewellery in question also appears to have been passed to Katherine Parr, sixth wife of Henry VIII, when she married the king in the summer of 1543. Given the jewel's appearance in portraits of the king's third and sixth wives, thus identifying it as property of the queen consort, it would make sense that the sitter in Holbein's miniature (and in the version housed in the Buccleuch Collection) was also a Tudor queen consort of England. In 1540, Katherine Howard became queen of England when she married Henry VIII at Oatlands Palace on 28 July 1540, in doing so displacing the king's fourth wife, Anne of Cleves - and yet Anne was also, briefly, queen consort in the year 1540, from January to July.

Above: Jane Seymour and Katherine Parr, third and sixth wives of Henry VIII

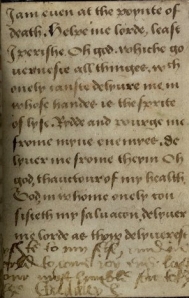

The Holbein miniature in the Royal Collection Trust was described in 1660-61, during the Restoration, as 'A small peice Inclineing of a woman after ye Dresse of Henry ye Eights wife by Peter Oliver'. The sitter in the miniature, however, was not formally identified at that point. By 1735-40, however, the version in the Buccleuch Collection (above) had been named as a likeness of Katherine Howard, an identification subsequently associated with the miniature in the Royal Collection Trust. Interestingly, when the Buccleuch version was identified during the eighteenth-century, it was also mooted as a portrait of Henry VIII's younger sister, Mary Tudor, queen consort of France (1496-1533). The costume, however, which dates to the 1540s, clearly rules out Henry's sister - who was also the grandmother of Lady Jane Grey - as the sitter in the portrait.

Unfortunately, the sitter's age was not inscribed on the portrait, which might have been helpful in assisting modern identifications of the sitter's identity. While Katherine has been the most popular candidate for the miniature, other sitters have also been proposed: chiefly, Lady Margaret Douglas, niece of Henry VIII and grandmother of James I of England, and Mary, Lady Monteagle, who served in the household of Jane Seymour.

Although Lacey Baldwin Smith, who published a biography of Katherine in 1961, did not discuss the miniature in his account of the queen's life, and thus offered no opinion as to whether or not it depicted her, Katherine's modern biographers have, by and large, accepted the miniature as a likeness of her, including myself, Josephine Wilkinson, Joanna Denny and Gareth Russell. Denny was, perhaps, the most strident; responding to Susan James' theory that the miniature depicts Margaret Douglas, Denny asserted that 'this does not explain why she [Margaret] is wearing the royal jewels.' Katherine's love of jewellery and fine clothing was recorded by contemporaries: the unknown Spanish author of The Chronicle of Henry VIII, for example, noted that 'the King had no wife who made him spend so much money in dresses and jewels as she did, who every day had some fresh caprice.' Alongside receiving jewels as presents from her besotted husband, Katherine made gifts of them to her female attendants and to her royal relatives, including her stepdaughters Mary and Elizabeth.

In his study of the six wives of Henry VIII, published in 2003, Dr David Starkey opined that the miniature is indeed a likeness of Katherine Howard, based on the inventory of her jewellery given to her when she married the king in July 1540. Starkey concluded that 'it can even be dated as a wedding portrait.' Specifically, the jewels given to Katherine that appear in the Holbein miniature include an 'upper biliment' or trimming for a French hood, 'of goldsmith work enamelled and garnished with 7 fair diamonds, 7 fair rubies and 7 fair pearls'; a 'square' necklace 'containing 29 rubies and 29 clusters of pearls being 4 pearls in every cluster' and an 'ouch', or pendant, 'of gold having a very fair table diamond and a very fair ruby with a long pearl hanging at the same'. The pendant also appears in portraits of Jane Seymour and Katherine Parr, as previously noted. Sir Roy Strong, at that time director of the National Portrait Gallery, also drew attention to the fact that the sitter wears the same jewel that appears in Holbein's portrait of Jane Seymour, thus suggesting that the miniature it is a likeness of Katherine Howard. Starkey may be incorrect, however, in suggesting that the portrait was undertaken in the summer of 1540; while she may have been misled in believing the miniature to be a likeness of Margaret Douglas, Susan James offered the convincing theory that the portrait was painted in the autumn or winter based on the style of the sitter's costume. Denny may, therefore, be more accurate in concluding that the portrait was 'very likely painted during her [Katherine's] first winter as queen'.

The costume itself, in which the sitter wears a French hood, may also lend itself to an identification with Katherine Howard. The French ambassador Charles Marillac, who observed the new queen while he was in attendance at court, wrote in September 1540, two months after her wedding, that 'she and all the Court ladies dress in French style'.

But was Katherine's portrait ever painted during her brief reign as queen? While I offer an extended discussion of her portraiture in my book Katherine Howard: Henry VIII's Slandered Queen, it is interesting to note curator and art historian Brett Dolman's suggestion that 'Catherine [Howard] left no documentary proof that her portrait was ever painted during her lifetime, and, perhaps, we are searching for the impossible.' In my book, I discuss other portraits associated with Katherine, including perhaps the most famous, now housed in the Toledo Museum of Art; it was formerly identified as a likeness of Henry VIII's fifth queen but is now generally agreed to be a portrait of Jane Seymour's younger sister Elizabeth, daughter-in-law of the king's chief minister Thomas Cromwell.

Dolman's recognition that Katherine may never have been painted during her brief queenship is significant in light of the recent suggestion made by art historian Franny Moyle, that the Holbein miniature is not a likeness of Katherine Howard, but a portrait of Anne of Cleves, Katherine's predecessor, who, as noted earlier, was also briefly queen consort of England in 1540, the year in which the portrait seems to have been painted. Moyle's theory is based on several pieces of evidence. Firstly, she notes that Holbein mounted the miniature on the four of diamonds, a playing card that Moyle believes to be significant, since Anne of Cleves was Henry VIII's fourth wife. Art historian Roland Hui, however, has challenged this point, however, in noting that a five of diamonds card appears on the back of Holbein's portrait of Jane Small (now housed in The Victoria and Albert Museum). Hui also clarified that 'part of a king' served as the backing to a miniature of Henry Brandon, the short-lived son of Henry VIII's favourite Charles, duke of Suffolk. In and of itself, therefore, the four of diamonds on the back of Holbein's miniature would not seem sufficient grounds on which to identify the sitter as Anne of Cleves.

Above top: Portrait of a Lady, perhaps Katherine Howard; Royal Collection Trust

Above below: Anne of Cleves, 1539

Historian Franny Moyle believes that both miniatures show the same sitter.

Moyle also argues that the sitter in the Holbein miniature shows an 'uncanny likeness' to Holbein's portrait of Anne (above), painted in 1539, shortly before her marriage to Henry VIII. Moyle draws attention to both sitters sharing a 'soporific expression', as well as distinctive heavy eyelids and thick eyebrows. Moreover, Moyle notes that the contemporary chronicler Edward Hall, who was an eyewitness to events at Henry VIII's court, described Anne the Sunday after her wedding as 'appareiled after the Englishe fassyon, with a Frenche whode [hood], whiche so set forth her beautie and good visage, that euery creature reioysed [rejoiced] to behold her.' Based on Hall's remark, Moyle suggests that, aware of Henry's initial lack of enthusiasm, Anne consciously set aside the - to English court observers, unfashionable - clothing that she had brought with her from Cleves and instead adopted the more stylish French dress favoured at court, in an attempt to please her husband. Taking this further, Moyle argues that the Holbein miniature was painted in the winter of 1540, perhaps in February, in order for the king to 'see a version of Anne that was more appealing.'

As noted earlier in this post, Dolman concluded that there is no documentary evidence that Katherine Howard's portrait was painted during her short tenure as queen. Equally, there is no evidence that Anne of Cleves sat for Holbein in the early months of 1540 wearing a French hood in an attempt to secure favour from her unenthusiastic husband, who had thus far failed to consummate their union; indeed, the marriage was annulled just months later, in July, having never been consummated. While Moyle is correct that Anne is a credible candidate for the sitter in the Holbein miniature on the grounds that there were two queen consorts in 1540, of which she was one, other elements of Moyle's argument are problematic.

Firstly, Moyle suggests that the Holbein miniature is unlikely to depict Katherine because it 'doesn't look like a child bride'. Katherine's date of birth is unknown. My research, which will be published in a forthcoming issue of The Royal Studies Journal, and expands on the arguments put forth in my book Katherine Howard: Henry VIII's Slandered Queen, indicates that she was born probably in 1523 or 1524, making her sixteen or seventeen when she married Henry VIII in 1540, while recent research suggests that Anne of Cleves was born on 28 June 1515, making her a few months short of her twenty-fifth birthday in January 1540 when her wedding took place at Greenwich Palace. Few historians today would characterise Katherine as 'a child bride', especially given how divergent early modern attitudes to childhood (and the life cycle, in general) were from modern perceptions of youth and adolescence. Interestingly, however, the unknown Spanish chronicler did characterise Katherine as 'a mere child', and the religious activist Richard Hilles identified her as a 'young girl' while describing the king's disaffection with Anne and his growing passion for Katherine. Either way, as noted earlier in this post, Holbein did not identify the sitter's age in the miniature, so it is impossible to ascertain how old the woman in the miniature was when she sat for the portrait. This arguably makes it pointless to speculate as to whether the sitter was 'a child bride' or not, as we have no way of knowing.

Secondly, Moyle indicates that the miniature, which apparently does not depict a beautiful woman, is more likely to portray Anne of Cleves, who was described by contemporaries as being 'of medium beauty', rather than Katherine Howard, whose beauty was said to be 'ravishing'. Conceptions of beauty in the sixteenth-century were, of course, very different to those prevalent in the twenty-first century Western world. Perhaps more to the point, surviving descriptions of both queens' physical charms are more complex than Moyle's belief would suggest. In the quotation of above, the chronicler Hall specifically drew attention to Anne's 'beautie and good visage'. The Cleves envoys, when arguing against a sea voyage to England in 1539 in the midst of preparations for Anne's wedding to the king, warned that a sea voyage would harm Anne's 'young and beautiful' appearance. While visiting Cleves, the English ambassadors reported widespread praise of Anne's beauty 'as well for the face, as for the whole body, above all other ladies excellent.' It was said that her beauty excelled that of Christina, duchess of Milan - another candidate for Henry VIII's hand in marriage - 'as the golden sun excelled the silver moon.' In December 1539, the lord admiral reported from Calais that he had heard reports of Anne's 'excellent beauty', which he perceived 'to be no less than was reported in very deed'. Clearly, then, it is somewhat misleading to suggest that Anne's beauty was widely reported as only 'medium'.

Likewise, reports of Katherine Howard's physical appearance were rather more complex than has been suggested. There is a widespread assumption among historians that she was the most attractive of Henry VIII's six consorts; her biographer Baldwin Smith noting in 1961, for example, that 'legend has it that she [Katherine] was Henry's most beautiful queen.' The unknown Spanish chronicler recorded that Katherine 'was more graceful and beautiful than any lady in the Court, or perhaps in the kingdom.' In his Metrical Visions, George Cavendish, who served in the household of Cardinal Wolsey, asserted that Katherine was 'floryshyng in youthe with beawtie freshe and pure'. By contrast, the French ambassador Marillac, who had described Anne of Cleves as being 'of medium beauty' and being neither as beautiful nor as young as everyone had been led to believe, depicted Katherine as a woman of mediocre beauty when he met her in the autumn of 1540. As Retha Warnicke has argued, 'a reasonable inference is that he [Marillac] considered Anne at least as pleasing in appearance as Katherine.' Arguably, it is problematic to identify the sitter in the Holbein miniature on the basis of differing, and somewhat contradictory, reports of the respective physical appearances of Anne of Cleves and Katherine Howard.

Above: Mary, Lady Monteagle (1510-before 1544) c. 1538-40, Royal Collection Trust

Finally, Moyle's belief that the sitter in the Holbein miniature is the same as that in Holbein's portrait of Anne created in 1539 due to shared physical features is also questionable. While both sitters do possess heavy eyelids and thick eyebrows, Anne does not appear to have had a double chin, while the sitter in the Holbein miniature does. It is also uncertain, mostly because Anne is facing the viewer, whether she shared the unknown sitter's nose. Perhaps most importantly of all, Anne's hair was described by the chronicler Hall on her wedding day as follows: 'hangyng downe, whych was fayre, yelowe and long'. The unknown sitter in the Holbein miniature does not have blonde hair, as Anne was said to have; instead, the colour can be described as auburn or light brown.

The portrait above is a likeness of Mary, Lady Monteagle (1510-before 1544), and is held by the Royal Collection Trust. The daughter of Charles Brandon, duke of Suffolk by his second wife, Anne Browne, Mary served in the household of Queen Jane Seymour, who presented her with gifts of jewellery as a sign of favour. Before 1527, Mary married Thomas Stanley, 2nd Baron Monteagle. On the basis of jewels given to her by Jane Seymour, it is sometimes asserted that the sitter in the Holbein miniature is Mary, Lady Monteagle, especially given notable similarities between her facial features and those in the Holbein miniature. Arguably, there are greater similarities between the sitters in these two portraits than there are between the Holbein miniature and Holbein's portrait of Anne of Cleves. If one were to position Mary's portrait next to the Holbein miniature, a case could be made that they display one and the same sitter.

The above portrait is now thought to depict Elizabeth Cromwell, sister of Jane Seymour and daughter-in-law of Thomas Cromwell (who was executed in 1540), but it was identified as a likeness of Katherine Howard in 1898 and received support from historians including David Starkey; in recent decades, however, its identification with Katherine has been convincingly and overwhelmingly challenged by historians. Nevertheless, on the basis of the sitter's jewellery and physical appearance, some writers continue to believe it depicts Katherine; for example, Alison Weir suggests that the portrait is 'probably of Katherine Howard, by Hans Holbein, at Toledo, Ohio'. While the sitter in the Toledo portrait does not necessarily display the heavy eyelids or thick eyebrows in the Holbein miniature, some have perceived similar physical features between the sitter in the Toledo portrait and the sitter in the Holbein miniature. Yet these alleged facial similarities are ungrounded if the portrait depicts Elizabeth Cromwell.

To conclude, the Holbein miniature of c. 1540, displayed at the top of this post, almost certainly depicts a queen consort of England in that year, of whom there are only two candidates: Anne of Cleves and Katherine Howard. Some historians have posited reasons for identifying an alternative candidate as the sitter - for example, Lady Margaret Douglas or Mary, Lady Monteagle - but these theories are far less convincing. Moyle's belief that the miniature is a likeness of Anne of Cleves undertaken in the early months of 1540 is interesting, but further research is necessary before it can be conclusively identified as a portrait of Anne during her six-month tenure as queen consort. The arguments given in this post, however, indicate that Moyle's theory is somewhat problematic. While, as Dolman recognises, there is no documentary evidence that Katherine Howard's portrait was painted during her queenship, there is also no evidence that Anne sat for a portrait wearing a French hood in the period after her wedding. The physical charms of both women were described by contemporaries in more complex ways than is sometimes recognised, and both women were described as wearing French attire, which in and of itself is insufficient to use as evidence for the sitter's identity. Perceptions of beauty, both in the sixteenth-century and now, are subjective, and perceived similarities in facial features between the Holbein miniature and Holbein's portrait of Anne undertaken in 1539 are also subjective, especially since the unknown sitter in miniature has also been thought to bear similarities in appearance to other sitters, notably Mary, Lady Monteagle and (probably) Elizabeth Cromwell. Perhaps the greatest drawback to the argument favouring Anne as the sitter, however, is the chronicler Hall's statement that Henry VIII's fourth queen had blonde hair: the sitter in the Holbein miniature clearly does not. The weight of evidence, then, would seem to lean more in favour, even if slightly, of Katherine Howard.

01.jpg)