On this day in history, 24 March 1603, arguably England's greatest queen if not monarch Elizabeth I died at Richmond Palace, six months before her seventieth birthday. Elizabeth had perhaps suffered from depression since about 1601, the year her former favourite Robert Devereux, Earl of Essex, was executed for treason. The deaths of close friends such as Katherine Howard, Countess of Nottingham, and loyal advisers such as William Cecil, Lord Burghley, probably contributed to the Queen's low moods and depression. Certainly, the last two or three years of her reign were, by the standards of Gloriana's Golden Age, uninspiring; even pessimistic.

In January 1603, as Tracy Borman in her successful Elizabeth's Woman notes, Elizabeth made the decision to move to Richmond Palace out of consideration for her rapidly declining health. Richmond Palace occupied a special place in the heart of the Tudors: it had been Henry VII's favourite palace. In March that year, however, the Queen fell into what Black terms "settled and unremovable melancholy". The Queen refused, however, to retire to bed; perhaps because she feared never waking up. When Robert Cecil, son of Lord Burghley and Elizabeth's chief minister, entreated his mistress to go to bed, she retorted charismatically: "the word must is not to be used to princes.. little man. Ye know I must died, and that makes ye so presumptuous". Obviously, Elizabeth's sharp tongue hadn't deserted her even on the brink of death!

Elizabeth did, however, eventually agree to retire to her bed and by 23 March it was clear that death was imminent. Archbishop Whitgift visited his mistress and entreated her to name her successor, an act she had famously refused to do for nearly five decades. She gestured with her hands, however, to signal that she agreed that James VI of Scotland, son of her former arch-enemy Queen Mary Stuart, should become king of England on her death. Between two and three in the morning the next day, the Queen died. John Manningham recorded poetically:

"This morning, about three o'clock her Majesty departed from this life, mildly like a lamb, easily like a ripe apple from a tree... Dr Parry told me he was present, and sent his prayers before her soul; and I doubt not but she is amongst the royal saints in heaven in eternal joys".

Above: Bette Davis as Elizabeth I. (left)

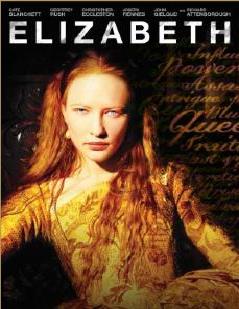

A more controversial portrayal. Cate Blanchett in "Elizabeth" (1998).

Historians speculate as to the cause of Elizabeth Tudor's death in 1603. Obviously, dying aged sixty-nine, she had lived to a great age most of her subjects never attained. G. J. Meyer suggests that the Queen could have died of anything of the following: bronchial infection that developed into pneumonia; streptococcus; the failure of one of her vital organs; or poisoning from ceruse (the mixture she used as her make-up). Meyer does agree, however, that the Queen's depression probably worsened whatever it was she was suffering from. On 28 April 1603, Elizabeth's funeral took place and she was interred in Westminster Abbey in a tomb to be shared with her infamous elder sister Mary I. The chronicler John Stow reported of the crowds gathered at the former Queen's funeral procession: "...there was such a general sighing, groaning and weeping as the like hath not been seen or known in the memory of man". England's great queen had died, bringing to an end the rule of the Tudors - England's ruling dynasty since 1485 - and perhaps the Golden Age.

Above: Elizabeth I's parents. King Henry VIII (1491-1547) and Queen Anne Boleyn (c.1501x1507-1536).

Elizabeth has regularly been viewed as England's greatest monarch. Her reign ushered in a Golden Age, when England's literary, artistic and musical achievements flourished and established it as a real player in European cultural exchange. Elizabeth's defeat of the Armada and her relative religious tolerance were both achievements that have been long appreciated by historians. A charismatic and yet mysterious woman, she remains a hugely popular subject among biographers, historians, filmmakers, dramatists, and novelists. It is perhaps Elizabeth's glamour that most appeals to a modern audience today. But it is perhaps the Queen's tolerance and desire for peace that most marks her out, in an age in which political and religious violence was endemic and monarchs frequently intolerant towards subjects they regarded as heretical or dissenting. As the Queen herself stated:

"...when wars and seditions with grievous persecutions have vexed almost all kings and countries round about me, my reign hath been peaceable, and my realm a receptacle to thy afflicted Church. The love of my people hath appeared firm, and the devices of my enemies frustrate".

It is also the mystery of Elizabeth that appeals. We don't know what she really looked like - her portraits were strictly controlled and censored by the government, and produced a prototype of how the Queen wished to appear rather than presenting what she viewed as unfavourable - and perhaps more truthful - renditions of her appearance. We do not know how she felt about her mother, Anne Boleyn. We do not know why she never married. We do not know her true attitudes to Mary Queen of Scots or her sister Mary. Perhaps most controversially of all, we do not know if she truly was a virgin queen. It is this mystery, glamour and charisma of Queen Elizabeth I that continues to make her such an exciting figure to study; especially in view of the cultural, political, religious and social achievements achieved in her reign as "Gloriana".