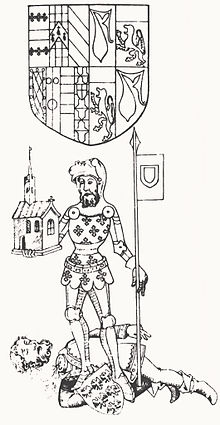

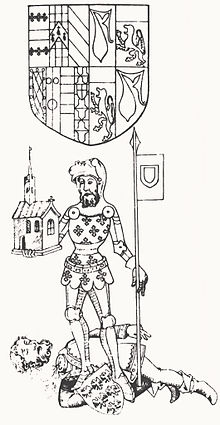

Above: the Earl of Warwick stands triumphant over the dead body of King Edward II's favourite, Piers Gaveston, first earl of Cornwall.

Above: the Earl of Warwick stands triumphant over the dead body of King Edward II's favourite, Piers Gaveston, first earl of Cornwall.

On 19 June 1312, the first earl of Cornwall, Piers Gaveston, was illegally put to death at Blacklow Hill near Warwick. He had been condemned to death by disaffected nobles, including the earl of Warwick, the earl of Lancaster, the earl of Hereford, and the earl of Arundel, for violating the terms of the Ordinances. Two Welshmen subsequently ran him through with a sword and then beheaded him. As Richard Cavendish claims in a 2012 article: Piers 'flew too high and paid the penalty'.

Piers was the son of a Gascon knight and had been born around 1284, who was loyal to the father of Edward II, Edward I. Piers became a member of the royal household at a young age and consequently met the future king there. Chroniclers described him as handsome, athletic, and well-mannered. Edward I had, reputedly, been impressed by Piers' conduct and martial skills and wanted him to serve as a model for his young son, the heir to the throne. Piers however came into conflict with the king, when a dispute occurred between the treasurer Walter Langton and the prince. Enraged, Edward I banished Piers and a host of other men from the prince's household. He was later exiled, but returned when Edward II acceded to the throne in 1307.

Historians have puzzled endlessly about the exact nature of Piers' relationship with Edward II. Piers was extremely close to the king. Although Cavendish terms it 'an extremely close friendship', he betrays a misunderstanding of medieval knowledge of sexual affairs, by suggesting that, although both Edward and Piers later fathered children with their spouses, they might have engaged in a bisexual affair with one affair. Scholars such as Kim Phillips and Barry Reay have convincingly demonstrated that modern notions of sexuality, including homo- and bisexuality, did not exist as such in the medieval period.

Above: Edward II controversially made his favourite, Piers Gaveston, earl of Cornwall in 1307.

Above: Edward II controversially made his favourite, Piers Gaveston, earl of Cornwall in 1307.

Chroniclers, however, speculated about Piers engaging in sex with the king. The Annales Paulini confirmed that Edward adored Gaveston 'beyond measure', while the Chronicle of the Civil Wars of Edward II suggested that, when he first saw Gaveston, the king felt such love for him that he 'tied himself to him against all mortals with an indissoluble bond of love'. The contemporary Vita Edwardi Secundi opined that 'I do not remember to have heard that one man so loved another... our king was... incapable of moderate favour'. Robert of Reading bluntly stated that Edward II enjoyed 'illicit and sinful unions'. In short, the wealth of evidence available supports J.S. Hamilton's suggestion that 'The love that the King felt for Piers Gaveston has been described as greater than the love of women. It still seems more likely that it was also stronger than the love of brother'.

Writers such as Lisa Hilton and Ian Mortimer have suggested that it is by no means certain that Edward engaged in sexual relations with Piers Gaveston (or other male favourites, for that matter), and Pierre Chaplais controversially argued that their relationship was probably closer to sworn brotherhood rather than a sexual relationship. As Phillips and Reay state, it is impossible to label either man homo- or bisexual, as popular writers, including Alison Weir, sometimes to do, as understandings of sexuality were extremely different in the medieval period. While it seems convincing that Edward and Piers had a sexual relationship, and perhaps loved one another, it is impossible to term either man 'non-heterosexual'.

Above: a representation of King Edward II.

Above: a representation of King Edward II.

In August 1307, Edward made Piers the earl of Cornwall, a decision which antagonised the barons, who resented Piers' foreign origins. When the king left England in early 1308 to marry the twelve-year old French princess Isabella, he appointed Gaveston regent in his place. When the king returned, he pointedly ignored his new bride in favour of Gaveston, who sat next to him at the coronation banquet. Eventually, disaffected barons forced the king's hand, and he was forced to exile the unpopular Gaveston in May 1308.

Despite this, Edward continued to reward his favourite, and he was appointed Lieutenant of Ireland. Inn some respects Gaveston enjoyed success in Ireland, fortifying the town of Newcastle McKynegan, for example. Eventually, when he felt that his nobles had perhaps mellowed towards Gaveston, Edward II recalled his favourite. By February 1310, however, some earls refused to attend parliament as long as Gaveston was present, so affronted were they by his arrogance and intimacy with the king. In November 1311, by which time the king had been forced to accept the Ordinances issued by the earls, Piers had again been exiled from England.

However, Gaveston returned at Christmas and was reunited with Edward in January 1312, probably at Knaresborough. The archbishop excommunicated Gaveston in March, and the barons decided to obtain hold of Gaveston once and for all. Eventually, he was executed on 19 June outside of Warwick. His body was left on the ground for some time, before Dominican friars brought it to the city of Oxford and it was eventually buried at the Dominican prior at Langley, following the securing of a papal absolution for Piers in January 1315 (he had, as noted, been excommunicated). The king reacted with anger and heartbreak at news of his favourite's (and possibly, lover's) death, but circumstances did not allow him to seek vengeance with the earls.

Above: Katherine Howard (left).

The letter Katherine supposedly wrote to the courtier Thomas Culpeper, perhaps in July 1541 (right).

Above: Katherine Howard (left).

The letter Katherine supposedly wrote to the courtier Thomas Culpeper, perhaps in July 1541 (right).

Aside from being the youngest wife of Henry VIII, Katherine Howard is probably best known for her supposed adulterous affair with the handsome courtier Sir Thomas Culpeper conducted in 1541. What many historians argue began as a mutual attraction quickly developed into a powerful and dangerous adulterous liaison which eventually ended in the deaths of both queen and subject. However, the nature of the meetings between Katherine and Culpeper are shrouded in mystery, uncertainty and controversy. Only Katherine and Culpeper - and perhaps Lady Jane Rochford, the queen's attendant who arranged the meetings - know what really happened in those fatal spring and summer months in 1541.

For most historians, it seems obvious that Katherine, an oversexed, even 'promiscuous' young girl, had sexual intercourse with Culpeper, who was noted for his gallantry and, later rumours alleged, even indulged in rape (although, as I argue in my book, it seems more likely that it was actually his elder brother, confusingly also named Thomas Culpeper, whom the rumours referred to). This is supported by evidence documented by contemporaries residing near to the court. The unknown Spanish chronicler of The Chronicle of Henry VIII, compiled perhaps ten years after the events it described, suggested that 'the devil put it into this queen's heart' to fall in love with the dashing Culpeper, who slipped the queen a note one day during dancing confessing his love for her. Both proclaimed their love for one another on the scaffold, with the queen supposedly stating: 'I die a queen, but I would rather die the wife of Culpeper'. The Catholic polemicist Nicholas Harpsfield depicted an adulterous Katherine, who was 'an harlot before he [Henry VIII] married her, and an adulteress after he married her'.

Modern historians largely agree. The bestselling popular writer Alison Weir wrote of Katherine's affair with Culpeper: 'Katherine had not only been playing with fire, but she had also been indiscreet about it, and incredibly foolish'. Antonia Fraser, in her 1992 biography of the six wives of Henry VIII, agrees: 'the repeated confessions and reports of clandestine meetings between a man notorious for his gallantry and a woman who was already sexually awakened really do not admit of any other explanation than adultery'. In his 2009 study of the Tudor queens, historian David Loades characterised Katherine as 'queen as whore'. This prevailing view has been consolidated in popular culture. In the popular TV series The Tudors (2007-10), Tamzin Merchant and Torrance Coombs depicted a headstrong young couple who engaged in sexual intercourse on a frequent basis early on in Katherine's marriage to the king. While Merchant portrayed a queen who appeared deeply in love with Culpeper, Coombs presented an unflattering portrayal of a manipulative, violent and scheming man who engaged in an affair with the queen as a means of attaining power and personal gain.

Above: Tamzin Merchant (left) as Queen Katherine and Torrance Coombs (right) as Thomas Culpeper in the television series The Tudors.

Above: Tamzin Merchant (left) as Queen Katherine and Torrance Coombs (right) as Thomas Culpeper in the television series The Tudors.

However, drawing on the seminal research of noted scholar Retha M. Warnicke, it is this article's contention that the relationship between Queen Katherine and Thomas Culpeper between April and September 1541 was, in reality, very different. It was not a carefree sexual liaison motivated either by love or recklessness, as most writers continue to believe. Thomas Culpeper was an experienced and savvy courtier who had served the king since the mid-1530s, when he had entered court as a page to Henry VIII before becoming a gentleman of the king's privy chamber, where the king ate, slept, and entertained indoors. Culpeper was, therefore, as close in proximity to Henry VIII as it was possible to get. Since Katherine had only arrived at court in the autumn of 1539, barely nine months or so before she became queen of England, Culpeper was vastly more experienced than her in court protocol and politics. He seems to have used that power and experience to his advantage, in manipulating the young queen, who found herself in a somewhat vulnerable position in the spring of 1541.

Katherine had had a sexual relationship with Francis Dereham in 1538, when she was aged around fifteen, and the aggressive Dereham seems to have been determined to marry Katherine, even making the treasonous suggestion that, once Henry VIII died, he would be sure to marry his young widow. In the spring of 1541, Dereham arrived at court and began openly boasting of his previous affair with Katherine. At this time, the king fell seriously ill and his life was despaired of. He shut his doors to everyone bar his doctors, including his young wife, whom he had previously spent the majority of his time with. As Warnicke suggests, it is therefore surely significant, in this highly charged atmosphere at court, that Culpeper began meeting with the queen at about the very time that both her former paramour was bragging of his sexual hold over her, and her ageing husband fell seriously ill. Since it was believed that the king might die, it has been credibly suggested that Culpeper began manipulating Katherine, perhaps having discovered details of her scandalous past, in the hope of acquiring greater power and position should Henry VIII suddenly die.

Above: Manipulative lover or abused victim?

Above: Manipulative lover or abused victim?

Often, Katherine's meetings with Culpeper have been portrayed as playful, sexually intimate encounters, comprised of high passion and devotion. The reality was very different. The surviving records demonstrate that the queen refused to meet Culpeper unless Lady Rochford was present as chaperone, and when Lady Rochford began moving away on one occasion to allow the two to speak privately, Katherine reprimanded her for leaving her alone in the company of Culpeper, and told her to come back. It has been credibly suggested that 'Culpeper's rendezvous with the queen gave him the means to threaten and manipulative her'. In the summer of 1541, the queen wrote Culpeper a letter. Often, it has been portrayed as a love letter, but the nervous, even afraid tone does not suggest passion, but rather, fear and anxiety. A passage of the letter has been removed in the interests of this article (a passage dealing with Katherine's messenger):

Master Culpeper,

I heartily recommend me unto you, praying you to send me word how that you do. It was showed me that you was sick, the which thing troubled me very much till such time that I hear from you praying you to send me word how that you do, for I never longed so much for a thing as I do to see you and to speak with you, the which I trust shall be shortly now. The which doth comfortly me very much when I think of it, and when I think again that you shall depart from me again it makes my heart to die to think what fortune I have that I cannot be always in your company. It my trust is always in you that you will be as you have promised me, and in that hope I trust upon still, praying you that you will come when my Lady Rochford is here for then I shall be best at leisure to be at your commandment...

yours as long as life endures,

Katheryn.

Traditionally, the queen's signature, 'yours as long as life endures', has been interpreted as a message of undying love, but as Warnicke recognises, Tudor letters typically closed with the statement 'by yours most bounden during my life', or something similar. Therefore, by changing the statement to 'yours as long as life endures', Katherine seems to have been hinting at her suffering, her anxiety, her worries that Culpeper would reveal her past to the king. 'Death and danger, not love and romance, were on her mind'. There was no evidence of love, passion or desire in this letter; no references to touching, kissing, caressing, etc. The queen was reported to be 'fearful and jittery' during their meetings, and admitted to Lady Rochford that she was terrified that these interviews would be discovered by others. Coupled with her insistence on Lady Rochford being present at all times, it seems clear that Katherine was meeting Culpeper only involuntarily, and not of her own free will.

Everyone knows how the story ends. Katherine and Culpeper were eventually discovered, while Francis Dereham and Lady Rochford were also imprisoned for their behaviour. A slew of Howard relatives and acquaintances of the queen were incarcerated in the Tower of London for concealing the truth about Katherine Howard's sexual past. Eventually, Dereham and Culpeper were convicted of adultery with the queen, although they both denied it, and they were executed in December 1541. Denying that she was guilty to the very end, the physically weak and frightened Katherine was beheaded on Tower Green on 13 February 1542 alongside her attendant Lady Rochford, who had reportedly gone insane.

Above: a fictional portrayal of Katherine Howard and Thomas Culpeper from Henry VIII (2003).

Above: a fictional portrayal of Katherine Howard and Thomas Culpeper from Henry VIII (2003).

Understanding of Tudor court politics and sixteenth-century beliefs surrounding gender and sexuality means that it is impossible to believe that Katherine Howard engaged in adultery with Thomas Culpeper. Katherine had endured something of a history of abuse. She had been seduced at a very young age by the grasping musician Henry Manox, before the aggressive Francis Dereham sexually manipulated her, perhaps even raping her. It is clear from surviving evidence that she had no real desire to meet with Thomas Culpeper and did so involuntarily and only in the presence of Lady Rochford, whom she perhaps trusted. This was not an affair of love, passion or desire. It was a relationship of power, manipulation and calculation that ended with both individuals' deaths.

Above: miniature portrait of Jane Seymour by Lucas Horenbout.

Above: miniature portrait of Jane Seymour by Lucas Horenbout.

On this day in history, 4 June 1536, Jane Seymour, third consort of Henry VIII of England, was proclaimed Queen of England at Greenwich Palace. The herald and chronicler Charles Wriothesley reported that:

'the 4th daie of June, being Whitsoundaie, the said Jane Seymor was proclaymed Queene at Greenwych, and went in procession, after the King, with a great traine of ladies followinge after her, and also ofred at masse as Queene, and began her howsehold that daie, dyning in her chamber of presence under the cloath of estate'. Later, the king's fifth and sixth wives, Katherine Howard and Katherine Parr, would also be shown to the court publicly as queen and would dine publicly under the cloth of estate.

Jane had married the king five days previously, at Whitehall Palace. Only eleven days prior to their marriage, the king's second wife and Jane's mistress, Queen Anne Boleyn, had been executed within the Tower of London on charges of adultery, incest, and plotting the king's death. Historians have speculated endlessly about how Jane felt about her mistress' death - did she take an active role in it? Did she encourage Henry to destroy his wife, even in so bloodthirsty a manner? Did she delight in Anne's death? Victorian historian Agnes Strickland thought so. Terming Jane's conduct 'shameless', she wrote thus: 'Jane saw murderous accusations got up against the queen, which finally brought her to the scaffold, yet she gave her hand to the regal ruffian before his wife's corpse was cold'. Modern historians such as David Starkey, Joanna Denny, and Eric Ives have similarly refrained from offering overly sympathetic or positive interpretations of Jane's behaviour.

Above: Queen Jane Seymour gave birth to Henry VIII's only legitimate son, Edward (above). Edward succeeded to the throne in 1547 as Edward VI on his father's death.

Above: Queen Jane Seymour gave birth to Henry VIII's only legitimate son, Edward (above). Edward succeeded to the throne in 1547 as Edward VI on his father's death.

Yet we have no clue how Jane really felt about the bloody and brutal events of spring 1536, when her mistress Anne Boleyn was dethroned and Jane was forced to step - literally - over her mistress' dead body to become queen of England. Whether she was personally willing or not, it cannot be denied that Jane's family were extremely ambitious and were determined that their relative should become queen in Anne's place. That they personally coached Jane on how to attract Henry seems likely.

Although Jane was presented to the English court as queen in June 1536, she was not crowned. There seem to have been plans for a coronation in the autumn of 1536, but an outbreak of plague derailed these plans. In the spring of 1537, the twenty-eight year old Jane fell pregnant, and that October gave birth to Henry VIII's only legitimate son, Edward, who became king of England aged nine years old in 1547 on his father's death. Tragically, however, Jane developed puerperal fever. The queen's attendants were blamed for allowing her to eat food that was unsuitable and to take cold. The queen developed septicaemia and she eventually became delirious. Just before midnight on 24 October, only twelve days after the birth of her son, Queen Jane died, aged twenty-nine. The king was grief-stricken, and wrote to his rival and fellow king, Francois of France, that: 'Divine Providence has mingled my joy with the bitterness of the death of her who brought me this happiness'.

That Henry VIII loved Jane Seymour and sincerely mourned her is borne out by the fact that not only did he and the court wear mourning for her until Easter 1538, but Jane continued to be represented in Tudor portraits, most famously featuring in a 1545 depiction of the king and his son - although Henry was, at that time, married to Katherine Parr. By virtue of providing the king with a male heir, Jane Seymour's important role in the Tudor dynasty was enshrined forever and appreciatively celebrated, as conveyed in this mural below, which portrays Henry VIII and Jane alongside his parents, Henry VII and Elizabeth of York. Henry VIII may have been drawn to Jane and loved her because she, in some respects, resembled his beloved mother: not only in looks, but also because both were docile, gentle, shrewd, peaceful, and loving. When King Henry died in 1547, he was buried at Windsor alongside Jane, whom he viewed as his one true wife.

Above: Henry VII and Elizabeth of York; Henry VIII and Jane Seymour.

Above: Henry VII and Elizabeth of York; Henry VIII and Jane Seymour.