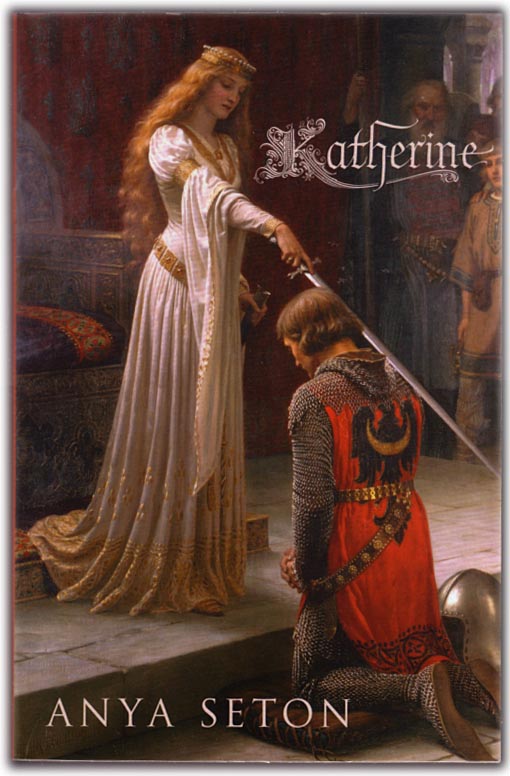

Above: Katherine by Anya Seton.

Katherine Swynford, duchess of Lancaster, is one of the most fascinating women in medieval English history. Most people know Katherine from Anya Seton's novel, published in 1954. Anya's Katherine is passionate, beguiling and ultimately loveable. The novel ripples with emotion, and its heroine is charismatic and memorable. At heart, it is a romantic novel, and the legendary relationship between Katherine and John of Gaunt is presented as one of passion. Whether this fictional depiction can be viewed as historically accurate is impossible to say, but Seton's reading is plausible, given that we know Katherine was John's mistress for many years before he finally married her. She became his third, and perhaps most beloved, wife.

As far as facts go, we know very little about the real woman, which is unsurprising given that she lived over six hundred years ago. Katherine Swynford was the daughter of the herald Paon de Roet, and she was born around 1350. Seton's novel depicts her as only having one sister, Philippa, but it is likely that she in fact had two (the other being Isabel). Katherine's sister Philippa, who may have been younger than Katherine, went on to marry the poet Geoffrey Chaucer, who is best known for his work The Canterbury Tales, a stunning insight into medieval English life that is replete with humour and wit.

Above: The tomb of Katherine next to that of her daughter Joan.

Katherine's first marriage was to the knight Hugh Swynford; their wedding probably occurred in 1366, when she was about sixteen. After their wedding, Hugh and Katherine resided at the manor of Kettlethorpe in Lincolnshire. By him, Katherine had three children. In the novel Katherine, the relationship between Hugh and Katherine is complex. They do experience affection for one another, but it is clear that Katherine's love for John of Gaunt takes precedence over any feelings she has for her husband Hugh. Later, Katherine became the governess of Philippa of Lancaster and Elizabeth of Lancaster, the daughters of John of Gaunt.

The love affair between Katherine and John is swathed in mystery, but it has been the subject of considerable attention ever since it took place. Artists, novelists and filmmakers have endlessly speculated about Katherine's relationship with John. In the novel, the two are acquainted at court and experience an instant, powerful attraction for one another that ends only with death. The truth, however, is much less certain. It may only have been when she became governess to his daughters that Katherine fell in love with John. It is entirely possible, moreover, that Katherine was more ambitious than has been traditionally thought. John of Gaunt was the third surviving son of King Edward III. While it may not have seemed likely that he would ever become king himself, he was Duke of Lancaster, probably the most powerful and influential nobleman in the kingdom. Wealth and riches were at his fingertips.

Above: A later portrait of John of Gaunt, duke of Lancaster.

By this time, John's first wife Blanche had died. The first duchess of Lancaster had been much-beloved; in life she had been strikingly beautiful, gracious and virtuous. Her young death was viewed as a sorrowful tragedy, and John was believed to have felt deep grief at her passing. His second marriage, to the Infanta Constance of Castile, was an entirely political match. John married her because he was ambitiously hoping to become King of Castile. The marriage ensured that the duke obtained a kingdom of his own, perhaps because he was aware that it was unlikely that he would become king of England. Constance died in 1394.

Katherine's love affair with John had begun shortly after Blanche's death. It was, however, to ruin Katherine's reputation: she was slandered as a 'scandalous' whore. The duke was highly unpopular himself, for he was viewed as unscrupulous and scheming. At some point, Katherine's husband died, and the unmarried Katherine's reputation suffered as a result of her relations with John. By him, she bore four children. Following Constance's death, John took the momentous step of marrying Katherine, thus legitimising their children. It was a true triumph for Katherine. No longer a disgraced whore, but a duchess by marriage, she attained what few royal mistresses could hope for: marriage with her royal lover. Tragically for the couple, John died only three years after their marriage. Katherine herself lived until 1403, when she died at the age of about fifty-three.

Above: Katherine Swynford's tomb.

Katherine Swynford's life is extraordinary, not simply because of her love affair with one of the most powerful men in the kingdom. She lived at a remarkable time. Katherine lived through the flowering of English literature; her brother-in-law was the famed poet Geoffrey Chaucer, and it is reasonable to expect that she read his works herself. She was a young woman growing up during the celebrated reign of Edward III, who has been seen as one of England's greatest monarchs. And she experienced momentous political conflict, as embodied in the Peasant's Revolt of 1381.

Perhaps Katherine's real importance and fascination, however, lies in her legacy. Through her marriage to John of Gaunt, which ensured that their children were declared legitimate, Katherine was the ancestress of the Tudor dynasty. We may know very little about the real woman's life, but Katherine Swynford has been immortalised in fiction as a passionate, charismatic and determined woman. A royal mistress and later duchess of Lancaster, her life will likely forever remain one of enduring interest.