The marriage between the first Yorkist king, Edward IV, and Elizabeth Wydeville was highly controversial in the fifteenth-century. There were doubts over its legitimacy, and some modern historians believe that Edward's first marriage to Lady Eleanor Butler rendered the Wydeville marriage invalid. This blog post does not seek to explore whether Edward's marriage to Elizabeth was valid or not. Rather, it is concerned with the offspring of the Wydeville marriage.

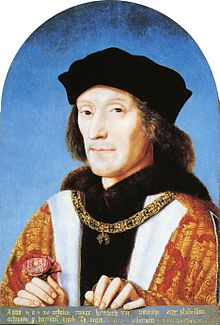

Queen Elizabeth proved to be a fertile bride. In nineteen years of marriage, she gave birth to ten children: seven daughters and three sons. All of the sons died young, and two of the daughters did not live to adulthood. The eldest child, Elizabeth, became Queen of England in the summer of 1485, when she married Henry VII, the first Tudor king. Her brother was Edward V, who had been imprisoned in the Tower of London with his younger brother Richard when their uncle, the duke of Gloucester, usurped the throne in 1483. Mystery surrounds the fates of the 'Princes in the Tower', as they came to be known. Most modern historians believe that they were likely dead by the autumn of 1483.

Queen Elizabeth Wydeville was close to her children, particularly her eldest daughter Elizabeth. This blog post explores the lives of the children of King Edward IV and Queen Elizabeth.

Elizabeth of York (1466-1503)

The eldest child of King Edward and Queen Elizabeth was a daughter. She was born at Westminster Palace on 11 February 1466, and was named for her mother. While young, Elizabeth was briefly betrothed to George Neville, first duke of Bedford. This was not the match that the king and queen had envisaged for their eldest daughter, but the match was proposed with a view to continuing the friendship between the house of York and the Neville earls of Warwick. When George's father joined forces with his brother, the 'Kingmaker' duke of Warwick, the betrothal was called off. In 1475, in alliance with Louis XI of France, King Edward arranged a betrothal between his daughter and Charles, the French dauphin. It would have been a splendid marriage for Elizabeth, had it have gone ahead, and it would have enabled her to become Queen of France. However, it was not to be. Elizabeth's father died in 1483, and following the accession of her uncle Richard, Elizabeth accompanied her mother into sanctuary, with her other siblings. A year later, Elizabeth left sanctuary with her sisters, and they arrived at court. It is likely that they resided in the household of Queen Anne. Rumours of the queen's imminent demise fuelled speculation that King Richard was planning on marrying his niece. Whether Elizabeth truly considered marrying Richard is a mystery, and has been furiously debated by historians. It is entirely likely that she did scheme to marry her uncle, but ultimately his death at Bosworth in 1485 compelled her to honour her prior agreement to marry Henry Tudor, who had become king.

Elizabeth and Henry, to all appearances, enjoyed a warm and loving marriage. Elizabeth gave birth to seven children; three of them survived to adulthood. She appears to have been a popular queen consort and was praised for her acts of intercession. Mystery surrounds much of Elizabeth's life. We do not know the true nature of her relations with her resourceful mother-in-law, Lady Margaret Beaufort. Nor do we know whether she really believed that her younger brothers had been murdered. Whether she loved Henry or not, she was a dutiful wife and a loving mother to their children. She died in 1503, on her thirty-seventh birthday. Her son, who later became Henry VIII, was said to have been devastated by her death.

Mary of York (1467-1482)

Mary was the second child of Edward and Elizabeth. She was born on 11 August 1467 at Windsor Castle. Very little is known about her. There were rumours during her childhood that she would marry John, the Danish king. In 1480, at the age of thirteen, she became a Lady of the Garter alongside her younger sister Cecily. Mary died on 23 May 1482 at the age of fourteen. She was buried at St. George's Chapel at Windsor Castle, where her parents would later be buried. Her early death meant that Mary did not experience the drama of the following year, when her father died, her brother was deposed and her uncle became king.

Cecily of York (1469-1507)

Cecily of York's life is one of drama. The events of her life suggest that she seems to have been a strong-minded, impulsive woman. Cecily was born at Westminster Palace on 20 March 1469, and was likely named after her grandmother, the duchess of York. At the age of seven, she was betrothed to the future James IV of Scotland. Cecily would have grown up believing, at least for a time, that it was her destiny to be Queen of Scotland. However, it was not to be. In 1482, when Cecily was thirteen, she was betrothed to Alexander Stewart, duke of Albany. However, the death of Edward IV the following year put paid to any hopes Cecily may have had of marrying Albany. On her uncle Richard III's orders, she and her siblings were declared illegitimate, on the grounds that the marriage of Edward and Elizabeth Wydeville was invalid. However, Richard knew that Cecily remained attractive as a prospective bride. To counter this, he arranged for her to marry Ralph Scrope of Upsall, a younger brother of Richard's supporter Thomas Scrope. It was surely not a match that Cecily had desired; given that she had been betrothed at one time to the heir to the Scottish crown, it is entirely possible that she was bitterly disappointed, perhaps even resentful.

Henry VII's accession, however, changed Cecily's fortunes. The Scrope marriage was annulled and, two years after Richard III's death, Cecily remarried. Her second husband was John Welles, first Viscount Welles, who was a maternal half-brother of Lady Margaret Beaufort and was, therefore, half-uncle to Henry VII. Again, it was probably not the match that Cecily had wanted, but it is possible that the couple were happy. They had two daughters, Elizabeth and Anne, both of whom died young. Viscount Welles died in around 1498.

It is in the aftermath of her second husband's death that we are able to gain an insight into Cecily's personality. One commentator reported that she chose to marry for a third time for 'comfort': perhaps she sought love, or stability. Her third husband was an obscure Lincolnshire esquire, Thomas Kyme. It seems to have been a love match. However, Cecily was reckless in failing to secure Henry VII's consent to the marriage, which she was required to do, as a member of the royal family. The king was furious and banished his sister-in-law from court. Lady Margaret, who appears to have been fond of Cecily, interceded for her and some of Cecily's lands were restored to her. Cecily died in 1507 at the age of thirty-eight, and she was buried at Hatfield, Hertfordshire.

Edward V (1470-1483?)

The eldest son of King Edward and Queen Elizabeth was born on 2 November 1470 in Westminster Abbey. The queen had sought sanctuary after the Lancastrians had forced the king to flee his realm. However, King Edward emerged victorious and the prince was brought out of sanctuary. He was created Prince of Wales the following year. Prince Edward was reputedly learned, diligent, and dignified.

The birth of a son to the royal couple was highly important: it brought security to them, and offered the promise of future prosperity as well as the continuation of the dynasty. However, it was not to be. When he was only twelve years old, Prince Edward became King Edward V, upon the unexpected death of his father. However, his uncle Richard seized the throne. Edward was lodged in the Tower of London alongside his younger brother Richard, duke of York. Like his siblings, the new king was declared illegitimate and unfit to succeed to the throne.

Mystery surrounds Edward's fate. Contemporaries speculated a great deal about what had happened to him. Some outright accused King Richard of murdering him and his brother. Others believed that the king had died in the Tower from illness. The majority of modern historians believe that Edward was dead by late 1483, which if true would mean that he never reached his fourteenth birthday (and possibly not his thirteenth). Edward V is one of the shortest reigning monarchs in English history.

Richard, duke of York (1473-1483?)

Richard was born on 17 August 1473 in Shrewsbury, and may have been named for his grandfather Richard, duke of York; alternatively, he may have been named for his uncle, Richard, duke of Gloucester. At the age of four, Prince Richard married the five-year-old Anne Mowbray, countess of Norfolk, at Westminster in January 1478. This appears utterly bizarre to modern readers. The marriage occurred on account of the king's determination to secure the Mowbray estates. Anne died in 1481, and her estates should have passed to William, Viscount Berkeley and to John, Lord Howard. However, an act was passed in 1483 that granted the Mowbray estates to Prince Richard for his lifetime, and to his heirs, if he had any, when he died. The whole episode was an example of King Edward IV's capacity for rapacity and ruthlessness when it came to acquiring greater wealth.

The declaration made in the spring of 1483, following Edward IV's death, that the children of the Wydeville marriage were illegitimate on account of their father's previous marriage to Lady Eleanor Talbot, rendered Prince Richard a bastard. The prince was escorted to the Tower of London, to join his brother, Edward V. Most historians believe that Richard was killed on the orders of King Richard; others suggest that he was put to death, but on another individual's orders: possibly Henry Tudor; possibly the duke of Buckingham; or possibly Lady Margaret Beaufort.

However, others believe that Richard escaped abroad. One line of thought posits that the pretender Perkin Warbeck, who was a menace to Henry VII, was actually Richard, duke of York, come back to claim his inheritance.

Anne of York (1475-1511)

Anne was born on 2 November 1475 at Westminster Palace. In the summer of 1480, her father signed a treaty agreement with Maximilian I, duke of Austria, and it was agreed that Anne would marry the duke's eldest son Philip. This would have been a most prestigious marriage for Anne, for it would have enabled her to become duchess of Burgundy. Following Richard III's accession, the nine-year-old Anne was betrothed to Thomas Howard (later the uncle of Anne Boleyn and Katherine Howard) in 1484. Even after Richard's death, Howard remained eager to marry Anne. They married at Westminster Abbey on 4 February 1495. None of their children survived.

Anne was close to her sister Queen Elizabeth, and like her sister Cecily, she played an important role in court ceremonies. She carried the chrisom at the christenings of her nephew Arthur, in 1486, and niece Margaret in 1489. Anne died on 23 November 1511 and was buried at Thetford Priory in Norfolk. Later, her body was moved to the Church of St Michael the Archangel in Framlingham.

Katherine of York (1479-1527)

Aside from her sister Elizabeth, Katherine of York made the best marriage of any of the York children. She was born on 14 August 1479 at Eltham Palace. In childhood, Katherine had been betrothed to Juan, the heir to the kingdoms of Castile and Aragon (he was the older brother of Katherine of Aragon). Upon Henry VII's accession, Katherine was betrothed to James Stewart, duke of Ross. The same agreement envisaged marrying Katherine's mother, the dowager queen Elizabeth Wydeville, to James III of Scotland. These plans came to nothing, and in 1495, the same year her sister Anne married Howard, Katherine married William Courtenay, earl of Devon.

Again, it may not have been the marriage that Katherine had wanted, but it ensured that she was a countess. They had three children: Henry (who was executed in 1539 for plotting against Henry VIII); Edward (who died young); and Margaret (who married Henry Somerset, earl of Worcester). Her husband died in 1511. Following his death, Katherine swore a voluntary vow of chastity in the presence of the bishop of London. She was reportedly favoured by her nephew Henry VIII, who 'brought her into a sure estate'. Katherine died on 15 November 1527 at Tiverton Castle, the last of Edward IV's children to die.

Bridget of York (1480-1517)

Bridget was the youngest child of King Edward and Queen Elizabeth. She was born on 10 November 1480 at Eltham Palace. It is likely that Bridget was named after St. Bridget of Sweden. It seems that the king and queen decided, while Bridget was still young, that their youngest daughter would follow a religious life. At an unknown date between 1486 and 1492, when she was between the ages of six and twelve, Bridget was entrusted to Dartford Priory in Kent. Her sister, Queen Elizabeth of York, continued to write to her and send messengers. Bridget attended the funeral of her mother, Elizabeth Wydeville, in 1492. She died in 1517, and in some respects is the most obscure of Edward IV's daughters.

Children who died young

Margaret of York (born and died 1472)

George, duke of Bedford (1477-1479)

Margaret of York was born on 10 April 1472 at Winchester Castle in Hampshire. She was likely named for her aunt, Margaret, duchess of Burgundy. Tragically, Margaret died at the age of only eight months, on 11 December 1472. She was buried in Westminster Abbey.

George of York was born in March 1477 at Windsor Castle. The following year, he was created duke of Bedford. The dukedom of Bedford had long been associated with the royal family. That same year, George was appointed lord lieutenant of Ireland. He died in 1479 at the age of two, perhaps from plague, and was buried in St George's Chapel at Windsor Castle, where his parents were later buried.