Above: Empress Matilda could, perhaps, have been England's first queen regnant.

Above: Empress Matilda could, perhaps, have been England's first queen regnant.

Medieval England experienced some spectacular rulers, both male and female. This was an age, in particular, of extraordinary and resourceful women: consider Eleanor of Aquitaine, queen of Henry II, who continued shaping government policy, escorting brides across Europe, and leading armies well into her seventies. Isabella of France, wife of Edward II, launched an invasion against her ineffectual husband alongside her lover, deposed the king, and was possibly involved in his later murder. Then there was Margaret of Anjou, who courageously took hold of the reins of government when her saintly if unassuming husband Henry VI fell into madness, and took a spirited and energetic role of leadership in the conflict known as the Wars of the Roses, so vividly depicted in the works of Shakespeare. Elizabeth Woodville was another courageous and strong-willed queen who fought for the Yorkist inheritance during the Wars of the Roses and was every bit as formidable as her adversary Margaret. All of these women have, to differing degrees, been remembered as 'she-wolves': powerful, determined women who seized the reins of power seen as correctly belonging to their husbands, defying contemporary expectations of females as weak, gentle and submissive beings.

But none of these women, with the exception, perhaps, of Margaret, has endured so negative a reputation as that of the Empress Matilda, daughter and heir of Henry I of England, and 'Lady of England'. Indeed, this spirited and determined woman could have, had circumstances gone her way, been England's first queen regnant, rather than the teenaged Lady Jane Grey enjoying that honour over four hundred years later, in 1553. Contemporary chroniclers and modern historians alike have remembered Matilda as a feisty, 'haughty' and arrogant woman who alienated her followers and provoked loathing in the citizens of London when she attempted to claim the crown she viewed as rightfully hers following her father's death. Yet, as historian Helen Castor compellingly suggests, such negative characterisations of Matilda 'were never used to describe any male member of her fearsomely domineering family; and they do not fit well with what we know of Matilda in the decades before and after that brief moment in 1141'. So who, then, was this fascinating and complex woman, a daughter, mother and wife of kings, who fought tenaciously but ill-fatedly to become the first queen regnant of England in the twelfth century?

Above: Twelfth-century portrayal of the wedding feast of Matilda and her first husband, Emperor Heinrich V of Germany.

Above: Twelfth-century portrayal of the wedding feast of Matilda and her first husband, Emperor Heinrich V of Germany.

Matilda was born in February 1102 at Sutton Courtenay in Oxfordshire as the eldest child, to Henry I, king of England and duke of Normandy, and his pious, beautiful wife Matilda of Scotland. Later, a son was born, William Adelin, who died in 1120 aged seventeen in a tragic incident involving the White Ship. Her brother's premature end was to have momentous consequences for Matilda's subsequent career. Her father also had twenty-two illegitimate children by other women. In 1108/9, when Matilda was around six years old, the German emperor sued for her hand in marriage, an attractive prospect to King Henry because it would bolster the prestige of the crown as well as strengthening England's links with the most preeminent European power. In a sense, it was the most successful marriage he could have achieved for his young daughter. Aged only eight years old, Matilda left England for Germany in February 1110.

The couple met at Liege before voyaging to Utrecht in the Netherlands where they were formally betrothed in April 1110. Three months later, Matilda was crowned Queen of the Romans at Mainz, and became known thereafter as the 'Empress Matilda', a lavish and supremely regal title and position that represented a considerable achievement for an eight-year old girl. Although she was some sixteen years younger than her twenty-four year old husband, it was to prove a successful and prosperous marriage. Matilda was educated in the customs, manners and culture of her new domains. In 1114, she was actually married to her husband, for twelve was the minimum age at which a female could marry.

Matilda was widely praised in these years, with no hint of the later abuse and hostility that would be directed toward her by her future English subjects. An anonymous chronicler at the German court described his Empress thus: 'a girl of noble character', 'distinguished and beautiful, who was held to bring glory and honour to both the Roman Empire and the English realm'. Orderic Vitalis tells us that Emperor Heinrich loved his new wife dearly, and so graceful, gentle and dignified in her queenly duties would Matilda be that her German subjects immortalised her as 'the good Matilda'. In these early years, she was hardly the 'she-wolf' later disparaged by hostile chroniclers.

It cannot be doubted that Matilda was both a dedicated wife and a successful queen. In 1118-9, for example, she sat in judgement at a court at Castrocaro near Ravenna, over the competing claims between a bishop and an abbey from Forli and Faenza over a local church. The Empress eventually decided in favour of the abbey. Shortly afterwards, Matilda's younger brother and heir to the English throne, William, died in the White Ship tragedy in November 1120. At eighteen years old, Matilda was now her father's heir.

Above: A fourteenth-century presentation of the White Ship disaster in the winter of 1120.

Above: A fourteenth-century presentation of the White Ship disaster in the winter of 1120.

While Matilda's marriage to the Emperor was in many ways a success, she failed to fulfil the vital requirement of her position by bearing her husband sons. Why no children were born to the royal couple remains something of a mystery. Neither were considered by contemporaries to be infertile, although it has been speculated that those at the time believed that the Emperor's sins against the Church were to account for the couple's childlessness. Heinrich eventually died of cancer in 1125, leaving his wife, still only twenty-three years of age, a widow. Matilda was now transformed into the most glittering of prizes, heiress as she was to the crown of England. Although Matilda was later besieged with offers of marriage from numerous German princes, she refused all of them, before departing for her homeland, England.

In the meantime, Matilda's father Henry I had remarried, following the death of the revered Matilda of Scotland in 1118. His new bride was Adeliza of Louvain, a year younger than her new stepdaughter the Empress. However, the royal couple did not have any children; meaning that, theoretically, Matilda remained her father's heir and successor to the English crown. If she succeeded, she would be England's first queen regnant. Henry formally acknowledged his daughter's unique position. At Christmas 1126, he ordered his barons to publicly recognise his daughter as heir to the throne, which they did the following January.

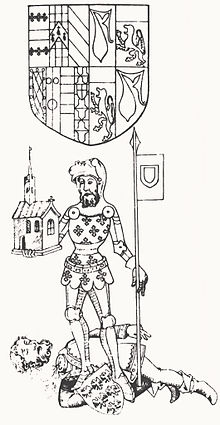

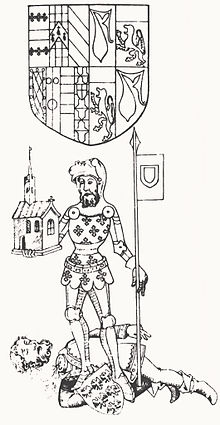

Above: A man Matilda did not wish to marry: her second husband, Geoffrey of Anjou.

Above: A man Matilda did not wish to marry: her second husband, Geoffrey of Anjou.

Although Henry I was, apparently, determined that his daughter Matilda should become England's next ruler in the wake of his death, this did not prevent him seeking a new husband for his twenty-five year old heir. In order to secure the southern borders of Normandy, he eventually arranged for her to marry the teenaged Geoffrey of Anjou, son and heir of Count Foulques. Nicknamed le Bel ('the Fair'), Matilda's prospective spouse was gorgeous, beautifully costumed and only fifteen years old. His face was said to glow 'like the flower of a lily, with rosy flush'. Despite his elegant charm and striking appearance, Matilda was decidedly unimpressed. This strong-willed, energetic and intelligent woman was not to be swayed by mere good looks and charm, and may have found the idea of a younger husband distinctly unappealing. Certainly, her reaction suggests this. Matilda was proud, and believed that marrying the son of a mere count served to diminish, even disparage, her status. The Archbishop of Tours, Hildebert, admonished her in letters and begged her to forgo her disobedience. Eventually, she reluctantly and unhappily agreed. So began a turbulent marriage.

Further difficulties were caused when Matilda's dowry was disputed. It was not specified when she would be able to inhabit the castles granted her in Normandy. It is perhaps instructive that soon after her marriage, the Empress returned to Normandy. In 1131, after a separation, the couple were finally reconciled, and if it had not been earlier, the marriage was consummated. Matilda proved a fertile bride (after her childless years with Emperor Heinrich); bearing her second husband three sons: Henry (who later became Henry II of England); Geoffrey (later Count of Nantes), and William (later Count of Poitou).

Above: A twelfth-century image of Matilda's eldest son, Henry, and his wife Eleanor of Aquitaine, as king and queen of England.

Above: A twelfth-century image of Matilda's eldest son, Henry, and his wife Eleanor of Aquitaine, as king and queen of England.

Everything changed in December 1135 when the king of England died. Matilda, now thirty-three, was set to become England's first female ruler, by virtue of her position as Henry's legal heir. Yet there had been difficulties in the previous years. She had experienced strained relations with her father, who perhaps feared her husband's desire to acquire more power in Normandy. Controversy surrounds Henry's plans for the succession on his deathbed. Sources favourable to the Empress confirmed that Henry reaffirmed his intent that she should succeed him, but hostile texts alleged that he had retracted his promise and had apologised to his barons for forcing them unwillingly to swear an oath of allegiance to his daughter.

Matilda's position gravely weakened her cause even before it had begun, for she was residing in Anjou with her husband when news reached her that her father had died. Matilda was by now pregnant for the third time, and it has been credibly suggested that her condition could have prevented her returning to England considerably sooner than she did. Stephen of Blois, Matilda's cousin, reacted in exactly the opposite manner. Dwelling in Boulogne, the count immediately left for England, determined to claim the crown. He had been close to the dead king, and it has been argued that his sex and proximity made him a more appealing monarch than his female cousin, who was not even in the country. On 26 December 1135, Stephen was crowned King of England. He had taken his opportunities, whereas Matilda had not.

Above: Stephen of Blois, king of England.

Above: Stephen of Blois, king of England.

In July 1136, Matilda delivered her third son, William, at Argentan. How she reacted with news of Stephen's accession is unknown, but she must have been shocked and appalled, at the very least. She may have beseeched the Bishop of Angers to garner support for her claim to the throne with the Pope but if she did, the Bishop was unsuccessful in doing so. Disputes and conflict continued in Normandy between the English king and Matilda, although a truce was later agreed between Stephen and Geoffrey.

Matilda's cause was immeasurably strengthened when her half-brother, Robert of Gloucester, decided to support her, promising her forces. In 1138, he had rebelled against the English king, thus instigating a civil war that was set to last for years. Geoffrey of Anjou took advantage of unrest and rebellion in England by reinvading Normandy. At the same time, King David of Scotland invaded the north of England, and promised support to the Empress simultaneously. Although Stephen travelled both north and west to quell disorder, and to some extent was successful in doing so, Matilda invaded in the summer of 1139, determined to attain the throne she believed was rightfully hers. So began what historians term 'the Anarchy'.

The former queen and stepmother to Matilda, Adeliza, in some ways instigated the rebellion by inviting her stepdaughter to land at Arundel Castle, on the south coast. In September, Matilda arrived with Robert with a force of 140 knights, and Matilda promptly departed for Arundel Castle while Robert headed northwest to Wallingford and Bristol, where he met Miles of Gloucester, the Constable of England who now supported the Empress. Stephen besieged the castle, trapping Matilda inside. Later, she was released, for unknown reasons.

Helen Castor has suggested that Matilda's sex strengthened her cause in that Stephen refused to face her in battle. The next few years saw protracted truces, armed rebellions, and heavy conflict, most notably the Battle of Lincoln in February 1141 which saw the defeat of King Stephen. He was later taken into custody by Robert of Gloucester. Matilda faced him triumphantly in person and incarcerated him in Bristol Castle. She then took steps to crown herself Queen of England, until now having been known as the 'Lady of England'. Stephen's brother and former enemy of the Empress, Bishop Henry, now renounced his support for his brother and defected to Matilda's side, in exchange for her promise that she would allow him control over Church affairs.

In Winchester at Easter 1141, Matilda was declared 'Lady of England and Normandy' by the assembled clergy, in what seems to have been a precursor to her coronation as queen regnant. The Empress then headed to London, but her position quickly became notably precarious. Forces loyal to Stephen and his wife remained close, and the citizens were visibly fearful about letting Matilda into the city. On 24 June, the city rose up against her. Matilda fled to Oxford just in the nick of time.

Most historians have suggested that it was Matilda's 'haughty', 'arrogant' temperament that so alienated the Londoners, that accounts for her ultimate failure to seize the crown. Henry of Huntingdon wrote that 'she was lifted up into an insufferable arrogance' and 'she alienated the hearts of almost everyone'. Yet, Helen Castor offers a more credible explanation of Matilda's difficulties given the uniqueness of her position and the difficulties she faced:

The truth of the matter was that Matilda found herself trapped. She urgently needed to show that she was a credible ruler... But when she sought to emulate her formidable father and her first husband, the two great kings whose rule she knew best, she encountered not awestruck obedience, but resentment of a 'haughtiness and insolence' that was deemed unnatural and unfeminine.

In a sense, then, it was Matilda's sex rather than necessarily her personal qualities which defeated her and rendered her unacceptable to her subjects. A female ruler was simply not an attractive prospect for the English. Like later queens Isabella of France and Margaret of Anjou, when Matilda tried to take the initiative and proactively shape policy, she was condemned and vilified for being 'manly', unfeminine, cruel, avaricious, arrogant and disdainful - all qualities viewed as the exact opposite of what a woman should be.

Above: Matilda's eldest son, Henry II of England.

Above: Matilda's eldest son, Henry II of England.

Because of this, Matilda never did become queen of England. Her initiative and determined attempts to take the crown were ultimately unsuccessful, in no small part influenced by the deaths of her most notable supporters, including Robert of Gloucester, in the late 1140s. However, her ambition was realised when Stephen accepted her eldest son, Henry, as his successor. He had taken a leading role in the later years of the civil war, reaching England in 1142 from the continent, before returning to Anjou two years later. The English Church supported Henry's claims to the English throne, as did Stephen's nobles and Louis VII of France, for the nobles were weary and disillusioned after years of bloody civil war, disorder and unrest. They wanted peace, and this was promised in the figure of the charismatic, resourceful and determined Henry.

Matilda lived to see Henry's succession and supported him energetically and faithfully, often acting as her son's representative in Normandy, where she now resided, and presiding over the Duchy's government. Like her daughter-in-law Eleanor of Aquitaine, Matilda remained fully involved well into old age. She was later involved in attempts at mediation between the king and the Archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas Becket. Matilda became increasingly pious during her later years, although one chronicler of Mont St. Jacques described her in her old age as 'of the stock of tyrants'. On 10 September 1167, aged sixty-five, the former Empress and 'Lady of England' died, and she was buried at the abbey of Bec-Hellouin under the high altar. Her tomb's epitaph included the lines: 'Great by birth, greater by marriage, greatest in her offspring: here lies Matilda, the daughter, wife, and mother of Henry'. Clearly, as were all women during this period in a patriarchal world, Matilda's life was remembered according to the role she had played in the lives of her male relatives. She was remembered for being a daughter, mother, and wife, rather than for being herself.

Or so it seemed. Most commentators, beginning in her lifetime and extending well into the present day, have instead focused on her apparently haughty, arrogant, even tyrannical nature, which supposedly doomed her attempts to take the crown of England and become its first ruling queen regnant. Yet scholars such as Helen Castor and Fiona Tolhurst have convincingly drawn attention to the fact that Matilda was criticised and disparaged for qualities that were revered and admired in men but found shocking and unacceptable in women: bravery, resourcefulness, determination, courage, ambition and drive. Had Matilda been a man, she would have been admired and celebrated, but her status as a woman condemned her as an 'unnatural' and 'unfeminine' virago who caused misery, discord and conflict in England, alienating all who met her. It is time for her reputation to be amended. She was ultimately extremely successful, not in becoming the first queen regnant of England in her own right, but by ensuring that, by virtue of who she was, her son Henry would become England's king following the death of her great rival and cousin, Stephen.

Above: Matilda.

Above: Matilda.

Above: Henry VIII of England.

Above: Henry VIII of England.

In the public mind at least, Henry VIII is usually depicted as a bloodthirsty tyrant, suspicious and paranoid, bloodthirsty and brutal, a man who did not hesitate to chop and change his wives when he felt like it, and who on more than one occasion put to death his closest ministers and friends. The numbers and facts speak for themselves: between 57,000 and 72,000 people were put to death during Henry's 38-year reign, including two of his wives (Anne Boleyn and Katherine Howard), his two closest advisers (Cardinal Thomas Wolsey and Thomas Cromwell), several nobles (the Duke of Buckingham, the Marquis of Exeter, the Countess of Salisbury, and the Earl of Surrey) and several especially prominent courtiers (including George Boleyn, Viscount Rochford). It was even rumoured in the mid-1530s that Henry was considering executing his eldest daughter, Mary, because she refused to acknowledge that her parents' marriage was incestuous and unlawful, and because she refused to swear the Oath of Supremacy. Mercifully, Mary retained her life, but the same could not be said for possibly as many as 71,000 others.

Was Henry VIII what we might call 'a bloodthirsty wife killer'? I decided to write this blog post having read Suzannah Lipscomb's intriguing and engrossing book 1536: The Year That Changed Henry VIII (2009). As Dr Lipscomb correctly asserts, in popular culture this most famous king is frequently portrayed as a bloodthirsty and cruel king who had six, possibly eight, wives; women whose lives came to notoriously premature ends. But the reality is undoubtedly more complex. Henry was not necessarily a capricious, shallow and fickle man who willingly surrendered his consorts to the executioner when he was bored of them, or when they failed to provide him with a much-desired son. As respected historian Alison Weir recognises in her study of the queens of Henry VIII: 'Taking into account the ever-present problem of the succession, it is impossible to dismiss Henry VIII as the cruel lecher of popular legend who changed wives whenever it pleased him'. Truth is, in fact, stranger than fiction.

Above: Anne Boleyn and Katherine Howard died prematurely, but were they married to 'a wife killer'?

Above: Anne Boleyn and Katherine Howard died prematurely, but were they married to 'a wife killer'?

This article considers whether Henry VIII can credibly be termed 'a wife killer' by looking at his two most infamous marriages, to Anne Boleyn and Katherine Howard, both of which ended on Tower Green. Henry's involvement with Anne was spectacular, for it catalysed the English Reformation as a result of breaking with the Roman Church, and it ushered in, as Lacey Baldwin Smith posits, the advent of the nation state. Married in 1533, Anne delivered arguably England's greatest monarch, Elizabeth I, in September that year. Boleyn biographers Eric Ives and G.W. Bernard both agree that Henry and Anne's marriage was volatile, 'sunshine and storms', although as Lipscomb intriguingly points out, observers commented on the royal couple's 'merry' times together more than they did with any of Henry's other wives. Although Anne was undoubtedly successful in promoting evangelicalism and was a responsible and enigmatic queen consort, she failed in her principal duty of giving birth to a much-longed for male heir. As everyone knows, in May 1536 she was accused of treason, incest and adultery with five men, and was executed as a result. Most scholars believe she was innocent of these crimes.

But, to turn to the question in hand: did ordering Anne Boleyn's execution render her husband, Henry VIII, 'a wife killer'? Lipscomb suggests not. Historical evidence credibly suggests that Anne was in high favour until barely three weeks before her death. Diplomatic correspondence indicates that Henry VIII was forcefully pressuring the European powers to recognise his second marriage and support Anne until as late as April 1536. It is therefore necessary to dispose of the myth that Anne's miscarriages caused Henry to tire of her. It is also a myth that Henry 'murdered' his wife because he had come to loathe and despise her. What, in fact, probably happened, as Lipscomb suggests in 1536, is that Anne's courtly behaviour with male courtiers caused her husband to believe that she was guilty of extramarital fidelity. She credibly suggests that Mark Smeaton, a lowly musician executed alongside the queen, was obsessed with Anne in a disturbing way perhaps reminiscent of a modern day stalker, and by extension admitted to sleeping with the queen as part of a misguided and disturbed fantasy. The queen then engaged in an exchange with Henry Norris, her husband's groom of the privy stool and personal favourite, in which she reprimanded him for seeking 'dead men's shoes' by looking to marry her when the king died. Speaking of Henry VIII's death was treason. Norris denied it and both he and Anne recognised their folly, the queen beseeching him to swear that she was a good woman as a result. When informed of these dangerous conversations, Henry VIII, shocked and in disbelief, ordered an investigation, which led to incriminations of several more men: Anne's own brother George, Francis Weston, William Brereton, and two others, Thomas Wyatt and Richard Page, who were later freed. They were all imprisoned, including the queen.

Henry's behaviour during Anne's imprisonment, condemnation and execution was bizarre. He experienced severe distress and pain, on the one hand, for example comforting his illegitimate son Henry Fitzroy, duke of Richmond, and telling him that only by God's favour had Fitzroy and Mary Tudor, the queen's stepdaughter, escaped Anne's poisoning. Yet he also demonstrated happiness, leading the imperial ambassador to conclude that the king was only too pleased that his queen had supposedly cuckolded him, for it left him free to marry his new love, Jane Seymour. Henry also took a morbid, even disturbing, interest in the practical details of Anne's execution, and Weir credibly conjectures that he ordered for a French swordsman to execute his wife five or six days before her trial - meaning that he always intended to have her beheaded. This might seemingly suggest Henry was a wife killer, but let us not forget that sixteenth century social and gender norms dictated Henry's responses. The queen's alleged adulteries posed a severe threat to his masculinity by suggesting he could neither rule his wife nor his household, two crucial signifiers of successful manhood. Worse still, Anne had allegedly ridiculed Henry's sexual prowess, laughing with her brother about it. Whether she had in fact done so or not, it is possible to understand Henry's severe actions. Humiliated, enraged and devastated, he acted in this manner to restore his manhood, for his wife had supposedly undermined and threatened the social order of their world. It is essential to recognise that Henry had not been nourishing hatred for Anne for most of their marriage. He publicly and earnestly supported her until three weeks before her death. He ordered an investigation, examinations, and public trials for both her and the men accused with her. Henry did not hastily put his wife and five innocent men to death in a fit of bloodthirsty revenge. Baldwin Smith's belief that Anne 'was dispatched with callous disregard' is, therefore, not necessarily correct.

Above: Suzannah Lipscomb suggests that Henry VIII ordered portraits like the one above to be painted of him, depicting him as resolute, courageous and stern and celebrating his masculine glory, so fatally undermined by two of his wives.

Above: Suzannah Lipscomb suggests that Henry VIII ordered portraits like the one above to be painted of him, depicting him as resolute, courageous and stern and celebrating his masculine glory, so fatally undermined by two of his wives.

While it is convincing to suggest that Henry VIII cannot be termed a wife killer regarding the downfall and death of Anne Boleyn, can the same be said of Katherine Howard? The grounds for designating Henry VIII a 'wife killer' regarding Katherine are even less firm. Henry adored his fifth consort, whom he married in the summer of 1540, and lavished jewellery and expensive presents on her. However, Katherine had an unsavoury past, and in the autumn of 1541, returning from a northern progress, the king was informed by Archbishop Thomas Cranmer of his queen's misdemeanours. The only evidence for Henry being 'a wife killer' comes in his initial response to this unwelcome news. When sitting with his Council, the king began weeping in a fit of sorrow, and called for a sword to execute that 'wicked woman' himself. Does this betray a bloodthirsty longing to be rid of a tainted wife? It is not necessarily that simple. Lipscomb convincingly indicates that after 1536, the year of Anne's execution, Henry became increasingly paranoid and suspicious, and reacted more and more brutally to personal betrayal. In a sense, he emerged as a tyrant. His response to Katherine Howard's behaviour can more plausibly be viewed as evidence of his views regarding betrayal. He refused to see Katherine ever again, and ordered her execution as a savage response to her betrayal, but which was fully justified and expected by the standards of the time. It was Katherine who was condemned for her behaviour, not her husband.

Again, historical facts need to be clearly understood here in order to explain Henry's response to Katherine's alleged adulteries. He was informed in November 1541 and that same month, the queen was imprisoned at Syon Abbey, while her supposed lovers and accomplice Lady Rochford were also incarcerated. The two men were executed the following month. However, it was only three months later, in February 1542, that Katherine and Lady Rochford were executed at the Tower of London. Again, this does not suggest that Henry VIII reacted hastily and bloodthirstily to news of his queen's betrayal. Some historians have conjectured that he considered saving Katherine's life and merely annulling the marriage, rather than beheading her, because he still loved her and was devoted to her. It is true that he did not grant his fifth queen and her servant a public trial. They were sentenced by Act of Attainder and were not given the chance to speak in their own defence. A unjust and, to our eyes, tyrannical move, perhaps motivated by personal vengeance and a desire to silence the woman he had once loved without letting her defend her actions, but in actual fact Henry VIII consistently used acts of attainder against those suspected of treason, as Lipscomb suggests, denying them the chance to speak out in open court. Katherine's relatives, the Earl of Surrey and the Duke of Norfolk, would both be sentenced to death this way.

Henry VIII loved Anne Boleyn and Katherine Howard intensely, as his love letters to Anne show and his lavish gifts of jewellery and costume to Katherine also prove. His emotional responses to news of their alleged adulteries also prove how much he cared for and loved them: he wept openly, cursed his bad luck, and became increasingly paranoid and dark as a result. As Philippa Gregory, the novelist, credibly suggests, after Anne's execution in 1536, the Tudor court became a darker place ruled by a suspicious and irascible monarch fearful of being betrayed at every corner. Henry did not rush hastily to condemn or kill his wives. He allowed Anne and her supposed lovers the chance to speak out in open court at their trials, and he showed initial signs of mercy toward Katherine Howard. But, as those who crossed Henry VIII found to their peril, the Tudor king responded brutally when he was, in his eyes, deceived and betrayed. This does not make him 'a wife killer', necessarily, but a man intensely concerned with maintaining and protecting his honour and sense of manhood, as were the majority of sixteenth-century men.

Above: Portrait of a woman thought to be Mary Boleyn, c. 1525.

Above: Portrait of a woman thought to be Mary Boleyn, c. 1525.

Philippa Gregory's bestselling novel The Other Boleyn Girl (2001) revitalised fascination with the Boleyn family and in particular Mary, the mysterious and unknown sister of Henry VIII's second queen. Mary Boleyn was the daughter of Sir Thomas Boleyn, born before 1502, and married William Carey in 1520 before briefly becoming Henry's mistress in the 1520s, before his attention turned to her enigmatic and attractive sister Anne. After she was banished from court in 1534 for making a clandestine second marriage, Mary survived the destruction of her family and died in obscurity in 1543 in her early forties.

Traditionally, historians have suggested that Mary was 'an infamous whore' who was the mistress of two kings, Francois I of France and Henry VIII of England. While it seems certain that Mary was indeed Henry's mistress, probably beginning in 1522 and ending before 1525 - Henry himself admitted to the affair and had to secure a papal dispensation in 1527 to marry the sister of a woman with whom he had had sexual intercourse - it is by no means certain that Mary was the French king's mistress. Indeed, historical evidence indicates that Mary never resided at the French court as a teenager.

Above: the Boleyn sisters, Anne (left) and Mary (right).

Above: the Boleyn sisters, Anne (left) and Mary (right).

As Retha M. Warnicke points out, there is no evidence that Mary Boleyn served as a maid of honour at the French court. In 1514, Anne Boleyn travelled to Paris to serve Mary Tudor, queen of France, and later transferred to the household of Claude, wife of Francois I, but there is no evidence that her sister was there. Household accounts documented a 'M. Boleyn', but it seems likely that the 'M' referred to 'Mademoiselle' or 'Mistress', rather than 'Mary'. Contemporaries commented on Anne's presence in France. For example, George Cavendish, gentleman usher to Cardinal Wolsey, stated: 'This gentlewoman, Mistress Anne Boleyn, being very young was sent into the realm of France'. No contemporaries, however, referred to Mary dwelling in France, where she supposedly acquired a reputation for promiscuity and licentiousness.

At the English court, it has been asserted, Mary was best known for her 'reputation in bed' (Lacey Baldwin Smith, 2013) and 'the evidence is overwhelming that Mary had a reputation for sexual improprieties' (Warnicke, 1985). As Alison Weir has thoughtfully demonstrated, however, there is in fact little to no evidence to support these views. Henry VIII's affair with Mary was discreet and secret, and few seem to have known of it. Mary remains a shadowy figure and we know nothing of her thoughts and feelings. How long her relationship with Henry lasted, and whether she truly loved him, is impossible to say. It is, however, certain that she was his mistress for a brief time in the 1520s and quite possibly bore him at least one, if not two, children.

Above: Francois I of France. It is unlikely that Mary Boleyn was ever his mistress.

Above: Francois I of France. It is unlikely that Mary Boleyn was ever his mistress.

While Mary was undoubtedly Henry VIII's lover for a time, it is almost certain that she was not the French king's mistress, despite persistent rumours to the contrary. In 1536, the French king informed Ridolfio Pio that he had known Mary in France 'per una grandissima ribalda et infame sopra tutte' - in other words, 'a great whore, infamous above all'. However, Mary never resided at the French court, so Francois cannot have insulted her in relation to her supposed sojourn there in the 1510s. Unlike Anne, who had departed for Europe to acquire a splendid education, Mary remained at home, probably Hever Castle, where she acquired a more traditional education befitting the status of an English gentlewoman.

So what then did Francois mean by his comment? Weir has pointed out that Pio was hostile to the Boleyns. Every member of the family was defamed and attacked by hostile political commentators who resented Anne and the rejection of Katherine of Aragon. Thomas Boleyn was slandered as heretical, grasping and scheming; his wife Elizabeth was defamed as a whore and former mistress of Henry VIII; George Boleyn was cast as a heretic and hedonist; and Anne was consistently portrayed as a whore, murderess, heretic and witch. It is therefore in keeping with this general defamation and slander of the Boleyn family that Mary, too, would have been dishonoured and abused by chroniclers and commentators hostile to their cause. Nicholas Sander, for example, slandered her in his works while abusing and defaming her sister Anne Boleyn.

It would therefore be ridiculous to accept such comments at face value. It is unlikely that Francois was referring to his own previous experiences with Mary. Possibly, as Warnicke credibly suggests, he only became acquainted with the new Queen of England's sister in 1532, when Mary accompanied Henry VIII and Anne to Calais. Francois may well have learned of Mary's former liaison with Henry and allowed it to cloud his view of her. His comment can hardly be read as admittance of a former relationship with Mary when she supposedly resided at his court as a teenager.

Aside from this one disparaging, insulting comment, there is no evidence that Mary was ever the mistress of the French king. There is no documentation of her stay in France, for the simple reason that she never served at the French court alongside her sister. In 1513, Anne Boleyn departed for Burgundy and later for France to serve in royal households. Her sister Mary, possibly because she was younger or possibly because she was less intellectual and brilliant than Anne, remained at home, before marrying William Carey in 1520. Shortly afterwards, she became the mistress of Henry VIII. We can say with some certainty that she was the lover of the English king, but we can equally be sure that she was never the mistress of his counterpart, the king of France.

Above: the Earl of Warwick stands triumphant over the dead body of King Edward II's favourite, Piers Gaveston, first earl of Cornwall.

Above: the Earl of Warwick stands triumphant over the dead body of King Edward II's favourite, Piers Gaveston, first earl of Cornwall.

On 19 June 1312, the first earl of Cornwall, Piers Gaveston, was illegally put to death at Blacklow Hill near Warwick. He had been condemned to death by disaffected nobles, including the earl of Warwick, the earl of Lancaster, the earl of Hereford, and the earl of Arundel, for violating the terms of the Ordinances. Two Welshmen subsequently ran him through with a sword and then beheaded him. As Richard Cavendish claims in a 2012 article: Piers 'flew too high and paid the penalty'.

Piers was the son of a Gascon knight and had been born around 1284, who was loyal to the father of Edward II, Edward I. Piers became a member of the royal household at a young age and consequently met the future king there. Chroniclers described him as handsome, athletic, and well-mannered. Edward I had, reputedly, been impressed by Piers' conduct and martial skills and wanted him to serve as a model for his young son, the heir to the throne. Piers however came into conflict with the king, when a dispute occurred between the treasurer Walter Langton and the prince. Enraged, Edward I banished Piers and a host of other men from the prince's household. He was later exiled, but returned when Edward II acceded to the throne in 1307.

Historians have puzzled endlessly about the exact nature of Piers' relationship with Edward II. Piers was extremely close to the king. Although Cavendish terms it 'an extremely close friendship', he betrays a misunderstanding of medieval knowledge of sexual affairs, by suggesting that, although both Edward and Piers later fathered children with their spouses, they might have engaged in a bisexual affair with one affair. Scholars such as Kim Phillips and Barry Reay have convincingly demonstrated that modern notions of sexuality, including homo- and bisexuality, did not exist as such in the medieval period.

Above: Edward II controversially made his favourite, Piers Gaveston, earl of Cornwall in 1307.

Above: Edward II controversially made his favourite, Piers Gaveston, earl of Cornwall in 1307.

Chroniclers, however, speculated about Piers engaging in sex with the king. The Annales Paulini confirmed that Edward adored Gaveston 'beyond measure', while the Chronicle of the Civil Wars of Edward II suggested that, when he first saw Gaveston, the king felt such love for him that he 'tied himself to him against all mortals with an indissoluble bond of love'. The contemporary Vita Edwardi Secundi opined that 'I do not remember to have heard that one man so loved another... our king was... incapable of moderate favour'. Robert of Reading bluntly stated that Edward II enjoyed 'illicit and sinful unions'. In short, the wealth of evidence available supports J.S. Hamilton's suggestion that 'The love that the King felt for Piers Gaveston has been described as greater than the love of women. It still seems more likely that it was also stronger than the love of brother'.

Writers such as Lisa Hilton and Ian Mortimer have suggested that it is by no means certain that Edward engaged in sexual relations with Piers Gaveston (or other male favourites, for that matter), and Pierre Chaplais controversially argued that their relationship was probably closer to sworn brotherhood rather than a sexual relationship. As Phillips and Reay state, it is impossible to label either man homo- or bisexual, as popular writers, including Alison Weir, sometimes to do, as understandings of sexuality were extremely different in the medieval period. While it seems convincing that Edward and Piers had a sexual relationship, and perhaps loved one another, it is impossible to term either man 'non-heterosexual'.

Above: a representation of King Edward II.

Above: a representation of King Edward II.

In August 1307, Edward made Piers the earl of Cornwall, a decision which antagonised the barons, who resented Piers' foreign origins. When the king left England in early 1308 to marry the twelve-year old French princess Isabella, he appointed Gaveston regent in his place. When the king returned, he pointedly ignored his new bride in favour of Gaveston, who sat next to him at the coronation banquet. Eventually, disaffected barons forced the king's hand, and he was forced to exile the unpopular Gaveston in May 1308.

Despite this, Edward continued to reward his favourite, and he was appointed Lieutenant of Ireland. Inn some respects Gaveston enjoyed success in Ireland, fortifying the town of Newcastle McKynegan, for example. Eventually, when he felt that his nobles had perhaps mellowed towards Gaveston, Edward II recalled his favourite. By February 1310, however, some earls refused to attend parliament as long as Gaveston was present, so affronted were they by his arrogance and intimacy with the king. In November 1311, by which time the king had been forced to accept the Ordinances issued by the earls, Piers had again been exiled from England.

However, Gaveston returned at Christmas and was reunited with Edward in January 1312, probably at Knaresborough. The archbishop excommunicated Gaveston in March, and the barons decided to obtain hold of Gaveston once and for all. Eventually, he was executed on 19 June outside of Warwick. His body was left on the ground for some time, before Dominican friars brought it to the city of Oxford and it was eventually buried at the Dominican prior at Langley, following the securing of a papal absolution for Piers in January 1315 (he had, as noted, been excommunicated). The king reacted with anger and heartbreak at news of his favourite's (and possibly, lover's) death, but circumstances did not allow him to seek vengeance with the earls.

Above: Katherine Howard (left).

The letter Katherine supposedly wrote to the courtier Thomas Culpeper, perhaps in July 1541 (right).

Above: Katherine Howard (left).

The letter Katherine supposedly wrote to the courtier Thomas Culpeper, perhaps in July 1541 (right).

Aside from being the youngest wife of Henry VIII, Katherine Howard is probably best known for her supposed adulterous affair with the handsome courtier Sir Thomas Culpeper conducted in 1541. What many historians argue began as a mutual attraction quickly developed into a powerful and dangerous adulterous liaison which eventually ended in the deaths of both queen and subject. However, the nature of the meetings between Katherine and Culpeper are shrouded in mystery, uncertainty and controversy. Only Katherine and Culpeper - and perhaps Lady Jane Rochford, the queen's attendant who arranged the meetings - know what really happened in those fatal spring and summer months in 1541.

For most historians, it seems obvious that Katherine, an oversexed, even 'promiscuous' young girl, had sexual intercourse with Culpeper, who was noted for his gallantry and, later rumours alleged, even indulged in rape (although, as I argue in my book, it seems more likely that it was actually his elder brother, confusingly also named Thomas Culpeper, whom the rumours referred to). This is supported by evidence documented by contemporaries residing near to the court. The unknown Spanish chronicler of The Chronicle of Henry VIII, compiled perhaps ten years after the events it described, suggested that 'the devil put it into this queen's heart' to fall in love with the dashing Culpeper, who slipped the queen a note one day during dancing confessing his love for her. Both proclaimed their love for one another on the scaffold, with the queen supposedly stating: 'I die a queen, but I would rather die the wife of Culpeper'. The Catholic polemicist Nicholas Harpsfield depicted an adulterous Katherine, who was 'an harlot before he [Henry VIII] married her, and an adulteress after he married her'.

Modern historians largely agree. The bestselling popular writer Alison Weir wrote of Katherine's affair with Culpeper: 'Katherine had not only been playing with fire, but she had also been indiscreet about it, and incredibly foolish'. Antonia Fraser, in her 1992 biography of the six wives of Henry VIII, agrees: 'the repeated confessions and reports of clandestine meetings between a man notorious for his gallantry and a woman who was already sexually awakened really do not admit of any other explanation than adultery'. In his 2009 study of the Tudor queens, historian David Loades characterised Katherine as 'queen as whore'. This prevailing view has been consolidated in popular culture. In the popular TV series The Tudors (2007-10), Tamzin Merchant and Torrance Coombs depicted a headstrong young couple who engaged in sexual intercourse on a frequent basis early on in Katherine's marriage to the king. While Merchant portrayed a queen who appeared deeply in love with Culpeper, Coombs presented an unflattering portrayal of a manipulative, violent and scheming man who engaged in an affair with the queen as a means of attaining power and personal gain.

Above: Tamzin Merchant (left) as Queen Katherine and Torrance Coombs (right) as Thomas Culpeper in the television series The Tudors.

Above: Tamzin Merchant (left) as Queen Katherine and Torrance Coombs (right) as Thomas Culpeper in the television series The Tudors.

However, drawing on the seminal research of noted scholar Retha M. Warnicke, it is this article's contention that the relationship between Queen Katherine and Thomas Culpeper between April and September 1541 was, in reality, very different. It was not a carefree sexual liaison motivated either by love or recklessness, as most writers continue to believe. Thomas Culpeper was an experienced and savvy courtier who had served the king since the mid-1530s, when he had entered court as a page to Henry VIII before becoming a gentleman of the king's privy chamber, where the king ate, slept, and entertained indoors. Culpeper was, therefore, as close in proximity to Henry VIII as it was possible to get. Since Katherine had only arrived at court in the autumn of 1539, barely nine months or so before she became queen of England, Culpeper was vastly more experienced than her in court protocol and politics. He seems to have used that power and experience to his advantage, in manipulating the young queen, who found herself in a somewhat vulnerable position in the spring of 1541.

Katherine had had a sexual relationship with Francis Dereham in 1538, when she was aged around fifteen, and the aggressive Dereham seems to have been determined to marry Katherine, even making the treasonous suggestion that, once Henry VIII died, he would be sure to marry his young widow. In the spring of 1541, Dereham arrived at court and began openly boasting of his previous affair with Katherine. At this time, the king fell seriously ill and his life was despaired of. He shut his doors to everyone bar his doctors, including his young wife, whom he had previously spent the majority of his time with. As Warnicke suggests, it is therefore surely significant, in this highly charged atmosphere at court, that Culpeper began meeting with the queen at about the very time that both her former paramour was bragging of his sexual hold over her, and her ageing husband fell seriously ill. Since it was believed that the king might die, it has been credibly suggested that Culpeper began manipulating Katherine, perhaps having discovered details of her scandalous past, in the hope of acquiring greater power and position should Henry VIII suddenly die.

Above: Manipulative lover or abused victim?

Above: Manipulative lover or abused victim?

Often, Katherine's meetings with Culpeper have been portrayed as playful, sexually intimate encounters, comprised of high passion and devotion. The reality was very different. The surviving records demonstrate that the queen refused to meet Culpeper unless Lady Rochford was present as chaperone, and when Lady Rochford began moving away on one occasion to allow the two to speak privately, Katherine reprimanded her for leaving her alone in the company of Culpeper, and told her to come back. It has been credibly suggested that 'Culpeper's rendezvous with the queen gave him the means to threaten and manipulative her'. In the summer of 1541, the queen wrote Culpeper a letter. Often, it has been portrayed as a love letter, but the nervous, even afraid tone does not suggest passion, but rather, fear and anxiety. A passage of the letter has been removed in the interests of this article (a passage dealing with Katherine's messenger):

Master Culpeper,

I heartily recommend me unto you, praying you to send me word how that you do. It was showed me that you was sick, the which thing troubled me very much till such time that I hear from you praying you to send me word how that you do, for I never longed so much for a thing as I do to see you and to speak with you, the which I trust shall be shortly now. The which doth comfortly me very much when I think of it, and when I think again that you shall depart from me again it makes my heart to die to think what fortune I have that I cannot be always in your company. It my trust is always in you that you will be as you have promised me, and in that hope I trust upon still, praying you that you will come when my Lady Rochford is here for then I shall be best at leisure to be at your commandment...

yours as long as life endures,

Katheryn.

Traditionally, the queen's signature, 'yours as long as life endures', has been interpreted as a message of undying love, but as Warnicke recognises, Tudor letters typically closed with the statement 'by yours most bounden during my life', or something similar. Therefore, by changing the statement to 'yours as long as life endures', Katherine seems to have been hinting at her suffering, her anxiety, her worries that Culpeper would reveal her past to the king. 'Death and danger, not love and romance, were on her mind'. There was no evidence of love, passion or desire in this letter; no references to touching, kissing, caressing, etc. The queen was reported to be 'fearful and jittery' during their meetings, and admitted to Lady Rochford that she was terrified that these interviews would be discovered by others. Coupled with her insistence on Lady Rochford being present at all times, it seems clear that Katherine was meeting Culpeper only involuntarily, and not of her own free will.

Everyone knows how the story ends. Katherine and Culpeper were eventually discovered, while Francis Dereham and Lady Rochford were also imprisoned for their behaviour. A slew of Howard relatives and acquaintances of the queen were incarcerated in the Tower of London for concealing the truth about Katherine Howard's sexual past. Eventually, Dereham and Culpeper were convicted of adultery with the queen, although they both denied it, and they were executed in December 1541. Denying that she was guilty to the very end, the physically weak and frightened Katherine was beheaded on Tower Green on 13 February 1542 alongside her attendant Lady Rochford, who had reportedly gone insane.

Above: a fictional portrayal of Katherine Howard and Thomas Culpeper from Henry VIII (2003).

Above: a fictional portrayal of Katherine Howard and Thomas Culpeper from Henry VIII (2003).

Understanding of Tudor court politics and sixteenth-century beliefs surrounding gender and sexuality means that it is impossible to believe that Katherine Howard engaged in adultery with Thomas Culpeper. Katherine had endured something of a history of abuse. She had been seduced at a very young age by the grasping musician Henry Manox, before the aggressive Francis Dereham sexually manipulated her, perhaps even raping her. It is clear from surviving evidence that she had no real desire to meet with Thomas Culpeper and did so involuntarily and only in the presence of Lady Rochford, whom she perhaps trusted. This was not an affair of love, passion or desire. It was a relationship of power, manipulation and calculation that ended with both individuals' deaths.

Above: miniature portrait of Jane Seymour by Lucas Horenbout.

Above: miniature portrait of Jane Seymour by Lucas Horenbout.

On this day in history, 4 June 1536, Jane Seymour, third consort of Henry VIII of England, was proclaimed Queen of England at Greenwich Palace. The herald and chronicler Charles Wriothesley reported that:

'the 4th daie of June, being Whitsoundaie, the said Jane Seymor was proclaymed Queene at Greenwych, and went in procession, after the King, with a great traine of ladies followinge after her, and also ofred at masse as Queene, and began her howsehold that daie, dyning in her chamber of presence under the cloath of estate'. Later, the king's fifth and sixth wives, Katherine Howard and Katherine Parr, would also be shown to the court publicly as queen and would dine publicly under the cloth of estate.

Jane had married the king five days previously, at Whitehall Palace. Only eleven days prior to their marriage, the king's second wife and Jane's mistress, Queen Anne Boleyn, had been executed within the Tower of London on charges of adultery, incest, and plotting the king's death. Historians have speculated endlessly about how Jane felt about her mistress' death - did she take an active role in it? Did she encourage Henry to destroy his wife, even in so bloodthirsty a manner? Did she delight in Anne's death? Victorian historian Agnes Strickland thought so. Terming Jane's conduct 'shameless', she wrote thus: 'Jane saw murderous accusations got up against the queen, which finally brought her to the scaffold, yet she gave her hand to the regal ruffian before his wife's corpse was cold'. Modern historians such as David Starkey, Joanna Denny, and Eric Ives have similarly refrained from offering overly sympathetic or positive interpretations of Jane's behaviour.

Above: Queen Jane Seymour gave birth to Henry VIII's only legitimate son, Edward (above). Edward succeeded to the throne in 1547 as Edward VI on his father's death.

Above: Queen Jane Seymour gave birth to Henry VIII's only legitimate son, Edward (above). Edward succeeded to the throne in 1547 as Edward VI on his father's death.

Yet we have no clue how Jane really felt about the bloody and brutal events of spring 1536, when her mistress Anne Boleyn was dethroned and Jane was forced to step - literally - over her mistress' dead body to become queen of England. Whether she was personally willing or not, it cannot be denied that Jane's family were extremely ambitious and were determined that their relative should become queen in Anne's place. That they personally coached Jane on how to attract Henry seems likely.

Although Jane was presented to the English court as queen in June 1536, she was not crowned. There seem to have been plans for a coronation in the autumn of 1536, but an outbreak of plague derailed these plans. In the spring of 1537, the twenty-eight year old Jane fell pregnant, and that October gave birth to Henry VIII's only legitimate son, Edward, who became king of England aged nine years old in 1547 on his father's death. Tragically, however, Jane developed puerperal fever. The queen's attendants were blamed for allowing her to eat food that was unsuitable and to take cold. The queen developed septicaemia and she eventually became delirious. Just before midnight on 24 October, only twelve days after the birth of her son, Queen Jane died, aged twenty-nine. The king was grief-stricken, and wrote to his rival and fellow king, Francois of France, that: 'Divine Providence has mingled my joy with the bitterness of the death of her who brought me this happiness'.

That Henry VIII loved Jane Seymour and sincerely mourned her is borne out by the fact that not only did he and the court wear mourning for her until Easter 1538, but Jane continued to be represented in Tudor portraits, most famously featuring in a 1545 depiction of the king and his son - although Henry was, at that time, married to Katherine Parr. By virtue of providing the king with a male heir, Jane Seymour's important role in the Tudor dynasty was enshrined forever and appreciatively celebrated, as conveyed in this mural below, which portrays Henry VIII and Jane alongside his parents, Henry VII and Elizabeth of York. Henry VIII may have been drawn to Jane and loved her because she, in some respects, resembled his beloved mother: not only in looks, but also because both were docile, gentle, shrewd, peaceful, and loving. When King Henry died in 1547, he was buried at Windsor alongside Jane, whom he viewed as his one true wife.

Above: Henry VII and Elizabeth of York; Henry VIII and Jane Seymour.

Above: Henry VII and Elizabeth of York; Henry VIII and Jane Seymour.