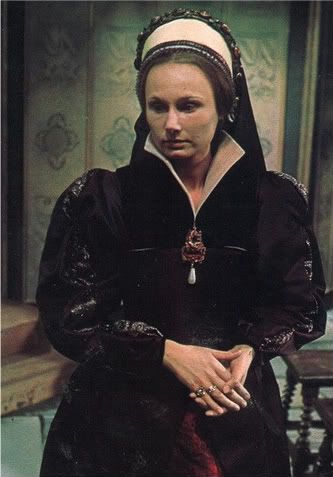

Above: Elizabeth of York (1466-1503).

Above: Elizabeth of York (1466-1503).

11 February was the most important day for Elizabeth of York, for she was born on this day in 1466 and died on this day, on her thirty-seventh birthday, in 1503. Elizabeth was the eldest daughter of the renowned first Yorkist king, Edward IV, and his beautiful if controversial queen Elizabeth Woodville. She was born at Westminster Palace and baptised in St Stephen's Chapel in Westminster Abbey.

Until 1470, aged four, Elizabeth was heir to the throne of England, but that year Queen Elizabeth bore her first son, the ill-fated Prince Edward who was - almost certainly - to die aged thirteen in 1483 as the imprisoned Edward V. In 1469 Elizabeth was betrothed to George Neville, son of the Marquess Montagu, as part of her father King Edward's attempts to build a strong relationship with the disaffected Nevilles, headed by the 'Kingmaker' Earl of Warwick.

Above: Elizabeth was the eldest daughter of King Edward of York (left) and Queen Elizabeth Woodville (right)

Above: Elizabeth was the eldest daughter of King Edward of York (left) and Queen Elizabeth Woodville (right).

In 1475, however, as part of the Treaty of Picquigny, it was agreed that Princess Elizabeth would marry the Dauphin Charles, with a jointure of £60,000 provided by the French king Louis XI. In 1483, when Elizabeth was aged seventeen, her father died, aged only forty-one. As Rosemary Horrox comments, Edward's death "transformed" the situation of his daughters. At the end of April Elizabeth's uncle Richard Duke of Gloucester took control of her twelve-year old brother and king Edward; leading the queen alongside her daughters and her younger son Richard to seek sanctuary in Westminster. In June 1483, Gloucester crowned himself as Richard III alongside his consort Anne Neville. He declared Edward's marriage to Elizabeth Woodville invalid, making their children, including Elizabeth, bastards and unfit to inherit the throne.

During the early months of Richard's reign, Elizabeth remained in sanctuary alongside her mother and siblings. Chroniclers suggested that there were attempts made to remove them from sanctuary and sail them from overseas, for "they were an obvious focus for political disaffection". The new King was unpopular amongst the majority of his English subjects, who viewed him as the likely culprit for the murder of the Princes in the Tower - although, of course, no-one knows to this day what happened to the two young boys. On Christmas Day 1483, the twenty-six year old pretender to the throne Henry Tudor swore an oath at Rennes Cathedral, promising to marry Elizabeth of York should he successfully attain the throne of England. Marriage to Elizabeth would provide him with a legitimate claim to the throne, for his own pretensions were somewhat dubious.

Above: Henry VIII was the son of Elizabeth of York by Henry VII. His mother's death, when Henry was aged eleven, appears to have profoundly affected him.

Above: Henry VIII was the son of Elizabeth of York by Henry VII. His mother's death, when Henry was aged eleven, appears to have profoundly affected him.

Alison Weir rightfully argues that, but for her gender, Elizabeth of York would have ruled England on the death of her uncle in battle at Bosworth in 1485, for she was the eldest child of Edward IV. Many believed, despite Richard's claims to the contrary, that he had entered into marriage with Elizabeth Woodville in good faith. However, rumours abounded that Elizabeth planned to marry not Henry Tudor, but her uncle King Richard. At Christmas 1484 - the girls had left sanctuary and had been welcomed at court - chroniclers were scandalised to see that Elizabeth was dressed in the same finery as Queen Anne, perhaps setting herself up as the queen's rival for the king's affections. Three months later, Anne died and rumours abounded that Richard had poisoned her in order to marry his nineteen-year old niece. Certainly, these rumours put paid to any hopes Richard may have had of marrying Elizabeth, and he realised that marriage to her would be a reckless, perhaps life-threatening, move. Weir, however, suspects that Elizabeth

had schemed to marry Richard, perhaps encouraged by her mother. Thus she can be termed an "enigma".

Richard was killed at Bosworth in August 1485 and the victor, Henry Tudor, crowned king, thus establishing the new Tudor dynasty. In January of the following year, the king selected Elizabeth as his consort and she was crowned late in 1487. In September 1486, she delivered her eldest son, the ill-fated Arthur who died aged fifteen. Elizabeth bore several children: Margaret (1489; becoming Queen of Scotland in 1503 and eventually grandmother to Mary Queen of Scots); Henry (1491; later Henry VIII); Elizabeth (1492; died aged three in 1495); Mary (1496; became Queen of France in 1514 but later married Charles Brandon and was thus ancestress to Lady Jane Grey); Edmund (1499; died 1500); and Katherine (born and died 1503). Like her mother, Elizabeth Woodville, the new Queen was extremely fertile.

Horrox comments that Elizabeth's political role as queen is uncertain, although Weir asserts that it was influential, remarking furthermore that her "role in history was crucial". She may have been overshadowed by her notorious mother-in-law Margaret Beaufort, but historians have disputed this more recently. But Elizabeth's crucial role as head of the Yorkist line, in a sense, alongside her position as first Tudor queen meant that her position was exceptionally important. It strengthened Henry VII's dubious claim to the throne, and meant that the Yorkists supported him when it might well have been in their interests not to do so.

Numerous myths and legends abound about the first Tudor queen. The popularity of Philippa Gregory's bestselling novels

The Cousins' War, including most pertinently

The White Queen and

The White Princess, mean that many people believe that Elizabeth, like her mother Elizabeth Woodville, engaged in witchcraft and supernatural actions to achieve her own desires; but this is almost certainly false. It is also suggested in these novels that Elizabeth's marriage to Henry was unhappy, that he raped her, for one thing, and she never loved him for another. But perhaps most spectacularly, it is suggested that Elizabeth's brother Richard survived, and she continued to support him, thus disobeying her husband. It should be borne in mind that, while it can never be known what exactly happened to Elizabeth's brothers, they

did disappear sometime in the autumn of 1483. Whose orders they were murdered on -

if they were, of course - cannot now be known, but traditional historians favour Richard III. I am very sceptical of Gregory's imaginative reworking of "history" and I believe that Elizabeth's marriage to Henry VII was strong, loving, and affectionate - as demonstrated by the death of their eldest son Arthur in 1502. Both parents were devastated, but both attempted to conceal their feelings in order to comfort the other. Eventually, both broke down in each other's arms. Clearly, the death of their heir devastated them. Instances such as this call into doubt Gregory's interpretation.

Above: Elizabeth of York as played by Freya Mavor in the BBC TV series The White Queen. In it, she is a witch and seductress who schemes to marry her uncle Richard III ... but the truth is probably less fantastical.

Above: Elizabeth of York as played by Freya Mavor in the BBC TV series The White Queen. In it, she is a witch and seductress who schemes to marry her uncle Richard III ... but the truth is probably less fantastical.

Elizabeth's reign as queen was successful in many respects, for she was a loyal consort and fertile bride who supported her husband faithfully. In the summer of 1502, she fell pregnant for the last time and entered confinement at the Tower of London in the winter. On 2 February, she bore a daughter, Katherine, who was sickly and sadly died soon afterwards. Nine days later, on 11 February, her thirty-seventh birthday, the queen died. She was mourned sincerely by her subjects and her husband King Henry appears to have been devastated. He did initiate marriage negotiations later in his reign, but these came to nothing and it is clear that he sincerely mourned the loss of his wife. The impact of her death on her children appears to have been monumental. Her 11-year old son, Henry, was particularly distraught, for he had been extremely close to his mother. Perhaps this accounts for his infamous attempts to find a successful marriage - trying to find the perfect woman who, perhaps consciously or unconsciously, resembled his mother as a dutiful wife, caring mother, and fertile bride.

Above: The last Tudor queen, Elizabeth I, was the granddaughter of her namesake and the first Tudor queen, Elizabeth of York.

Above: The last Tudor queen, Elizabeth I, was the granddaughter of her namesake and the first Tudor queen, Elizabeth of York.