The fate of the two Princes in the Tower, the eldest sons of Edward IV and his queen Elizabeth Woodville, is one of the greatest mysteries in history. Shrouded in controversy and mystery, historians and researchers fiercely disagree as to who was responsible for their deaths; debating as to whether both princes died; whether one, or both, in fact survived; and, unsurprisingly, this scandal has impacted profoundly on those associated with it, including two English kings, Richard III and Henry VII.

This article will examine the events which led to Richard III's accession and will explore the fate of the two Princes, considering the main suspects for their murders - if, that is, they were even murdered at all. The surviving evidence is intriguing, but entirely contradictory, and one has to take into account the political, social and dynastic bias of the writer, whether it was a Tudor apologist bent on demonising Richard, or a contemporary observer writing in a foreign country, detached from English events.

It was a shock for everyone when Edward IV died aged forty-one in April 1483, allegedly of a fever. This Yorkist king's reign had seen comparative peace and tranquillity in England following the dynastic troubles which had plagued the 1460s and 1470s, known by the later name Wars of the Roses. Edward had fathered at least 8 children with his queen Elizabeth, of whom his eldest son, Edward, aged twelve, had been heir and now England's king. However, the fact that the new king was a minor spelt trouble for contemporaries, for the rule of minor kings led inevitably to greater factional conflict and fierce rivalry over control of the child king. This, perhaps, may have greatly influenced the actions of both Edward's mother and his uncle, Richard duke of Gloucester.

In May 1483 the new king arrived in London for his coronation, weeks after the death of his father, and was accommodated in the royal residence of the Tower of London, while his younger brother Richard resided in sanctuary with his mother the queen and several of his sisters. They had journeyed there after hearing alarming news which suggested that Elizabeth's brother-in-law, Richard of Gloucester, had intercepted the king's journey from Ludlow in Wales and had seized the king's uncle Anthony Woodville and the queen's youngest son by her first marriage Richard Grey.

It seems certain that Richard of Gloucester feared for his own future, for the Woodvilles were powerful, greedy and notoriously intolerant. He may also have genuinely believed that his brother Edward's marriage to Elizabeth was invalid, for he claimed that it had been brought about by witchcraft and sorcery, and also suggested that Edward had in fact been previously precontracted to one Eleanor Butler, which meant that Elizabeth Woodville was never his lawful wife. Consequently, their children were illegitimate and not fit to inherit the throne of England. By this thinking, then, Richard of Gloucester was England's rightful king.

It is essential to critically examine later Tudor propaganda, which alleged that Richard III was a monster and a murderer. I, personally, do not believe that the moment King Edward died, Richard, as a scheming and essentially evil character, decided to seize the throne of England and murder his nephews. I believe that he genuinely feared the Woodvilles and, consequently, was scared for his own future, and it is entirely possible that he did believe that his brother's marriage to Elizabeth was invalid by reason of his earlier pre-contract. If this was true, then Richard was entitled to be king of England, as shocking as it may seem.

As Sarah Gristwood writes in her book Blood Sisters (2012):

"The majority of historians from Vergil and More onwards have believed that Richard III murdered his nephews; and thanks largely to Shakespeare, it has become the accepted view among many who care nothing for history. A vocal minority are utterly convinced he was not guilty, while propounding various alternative versions of the boys' fate. Others again believe it is virtually impossible to be certain, which makes it wrong to declare Richard guilty. In that uncertainty the writer's most honourable option is simply to present both the few known facts, and the relevant theories".

Contemporary historians fiercely and angrily dispute who killed the Princes in the Tower - as Gristwood says, most continue to believe, subscribing to persuasive Tudor propaganda, that it was their evil uncle, the hunchbacked and deformed Richard III (although the recent excavation at Leicester somewhat disproves this). Others, however, suggest it was someone entirely different. So what is the 'truth', if that can even ever be recovered?

One needs to put the events in context. Having seized the throne, Richard ordered it to be preached by a Dr Shaa at St Paul's Cross that Edward IV's marriage was invalid, rendering all his children (including his daughters living in sanctuary) illegitimate. By all accounts, what we know is that the Princes were last seen, for certain, playing in the grounds of the Tower in the summer of 1483 (the younger prince, Richard, having been sent out of sanctuary by a very reluctant Queen Elizabeth to join his brother in the Tower). Dominic Mancini stated that both princes 'were withdrawn in the inner apartments of the Tower proper, and day by day began to be seen more rarely behind the bars and windows, till at length they ceased to appear altogether'. In 1674, ominously, two skeletons were discovered under the staircase leading to the chapel within the Tower of London, and in 1933 the grave was opened (the two bodies having been buried, on the orders of Charles II, in Westminster Abbey), and the skeletons were determined to be those of two young children, aged about seven to eleven and eleven to thirteen. The two princes, if they died in 1483, would have been aged 12 and 10. Moreover, the fact that they were buried in Westminster Abbey, where royals were traditionally buried, indicates that, at least in the seventeenth century, the king and others believed the bodies to be of the princes.

So, firstly, it would be wise to consider the main suspect: Richard III. Some have argued that he had no need to kill his nephews, for he had already had them declared illegitimate - since they were bastards, neither could inherit the throne, so why should he need to have them dead when they were safely imprisoned? But, as historian Amy Licence notes: '... the princes' royal blood made them dangerous claimants to the throne, to whom many of their father's former staff would prove unfailingly loyal... Richard may have hoped that the problem of the two little boys may simply have disappeared. They did, but the problem didn't.'

Those who believe that Richard had no need to kill his nephews are somewhat misguided, for one needs only to consider the bloodshed of the Wars of the Roses to understand just why he may have felt he would only be secure with both boys dead. While they were alive and imprisoned, they would always be the focus for future rebellions which aimed to restore either boy to the throne as the rightful king, and one only needs to look at the example of Richard's brother Edward, who had had King Henry VI killed on his orders, obviously not feeling secure enough about his own claim to the throne. Edward had also had his own brother George duke of Clarence executed for treason - family connections did not prevent execution. It is possible that Richard ordered a loyal servant to dispose of his two princes, as suggested in Shakespeare's play. The suspect, for a long time, has been Sir James Tyrell, for he is known to have made a confession in 1502 which admitted that he had killed the two princes. This Tyrell was actually in London in the late summer and early autumn of 1483, when the boys were last seen alive for certain. Moreover, Licence suggests that, when Richard discovered that a loyal servant, perhaps Tyrell, had murdered both boys, he may have visited Canterbury Cathedral soon afterwards to make his peace with God, as a highly religious man.

There is evidence to suggest that Tyrell was the murderer of the princes, although since it was produced much later by observers writing in the Tudor age and thus hostile to Richard, it must be regarded as suspect. Polydore Vergil, who loathed Richard, claimed that Tyrell 'rode sorrowfully to London' to commit the deed on the orders of King Richard, while Richard himself later spread rumours of his nephews' deaths in the hope that it would discourage future rebellion. Thomas More, who vilified Richard to a shocking degree, also claimed that Tyrell had murdered the boys on Richard's orders, before confessing to his crime in the reign of Henry VII.

It seems that the most compelling reason to believe Richard was guilty of his nephews' deaths was the simple fact that he never publicly produced them, to prove that they were still alive, and to counter rumours which spoke of their murders. Furthermore, Richard promised the safety and security of the princes' sisters, but he gave no such assurances for their brothers, which suggests that they had been done away with by this time. Henry VII, when he acceded to the throne, accused the former king of "shedding of Infants blood" in a Bill of Attainder brought against the dead Richard, which probably directly accuses him of the Princes' murders. The Danzig Chronicle of 1483 alleged that 'Later this summer [1483] Richard the king's brother seized power and had his brother's children killed, and the queen secretly put away'. The French chancellor Guillame de Rochefort, in a speech on 15 January 1484, recounted how Edward IV's sons 'have been put to death with impunity, and the royal crown transferred to their murderer by the favour of the people'.

Many modern historians, including Alison Weir, Michael Hicks, and David Starkey, agree that Richard was the culprit. Further rumours alleged: Richard 'put to death the children of King Edward, for which cause he lost the hearts of the people. And thereupon many gentlemen intended his destruction'. The major problem is, however, that much of the surviving evidence which suggests Richard was the culprit was produced in the Tudor age, when Richard was vilified as a tyrant and a monster, and was therefore hardly objective. For instance, the historian Bernard Andre, writing in the sixteenth century, claimed: 'the entire land was convulsed with sobbing and anguish. The nobles of the kingdom, fearful of their lives, wondered what might be done against the danger. Faithful to the tyrant [Richard] in word, they remained distant in heart'. Philippe de Commines categorically confirmed that Richard III was responsible for the princes' deaths.

The fifteenth century was a troubled age, comprised of dynastic conflict, murder, treason and betrayal. Richard III would not have been unusual had he put to death his own relatives. Let us consider the fact that there were at least 5 other monarchs around this time who did the same thing:

Edward IV - put to death his own brother, George duke of Clarence, and probably ordered Henry VI's murder.

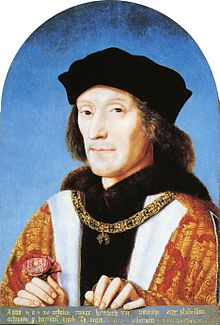

Henry VII - put to death his wife's relatives Edward earl of Warwick and Edmund earl of Suffolk.

Henry VIII - executed the 'White Rose' faction (members of the Pole family); also executed 2 of his queens.

Mary I - executed her own cousin, Lady Jane Grey.

Elizabeth I - executed her cousin and rival Mary Queen of Scots.

It would not have been unusual if Richard had ordered the murder of his 2 nephews. I do not subscribe to the Tudor propaganda which presents Richard as evil, deformed, corrupt and ungodly. But I do think that, in this period, a person did not have to be evil to commit an act of murder.

However, there might be other evidence which intriguingly suggests that Richard was not, in fact, the culprit for the murders of his nephews. Some have suggested that it was, in fact, Margaret Beaufort, mother of Henry VII. She would clearly have had a motive, for if the two princes were to die, then her son would have an even stronger claim to the English throne. He was betrothed to their sister Elizabeth of York, yet if they remained alive, they would both have a greater claim to be king than he would, even if he were to marry their sister. The seventeenth-century antiquary George Buck apparently read 'in an old manuscript book' how it was believed that Margaret and her friend Bishop Morton 'conspiring the deaths of the sons of King Edward and some others, resolved that these treacheries should be executed by poison and by sorcery'. Helen Maurer, a historian, also favours Margaret as the culprit.

However, Buck was one of Richard III's earliest and most vocal defenders, and so would have claimed that it was someone from the enemy camp who had committed such a shocking deed. It is also noteworthy, as Weir notes, that Richard's own relatives never accused Margaret of murdering the princes - Margaret of York, his elder sister and former Duchess of Burgundy, who loathed Henry VII, never accused Margaret, while she was not even named by other contemporaries. Furthermore, we do not even know Margaret's whereabouts during the summer of 1483 for certain - she may not have been in London at the time. Margaret also, at this time, was probably in a secret alliance with Queen Elizabeth, plotting to marry her son Henry to Elizabeth's daughter, and if Margaret was simultaneously planning to murder Elizabeth's sons, it is inconceivable that the Queen would have co-operated and worked together with Margaret.

Was the murderer in fact Henry Tudor, future king of England? He was not actually residing in England in the summer and autumn of 1483, instead being a fugitive in Brittany as he plotted to usurp the throne from Richard with the aid of his mother. Gristwood seems to believe that he may possibly be responsible:

'If Henry were to bolster his own genealogically weak claim with that of Elizabeth of York, he needed the princes dead. If the whole family were declared illegitimate, then Elizabeth had no claim. If they were legitimate, her brothers' claim would take precedence over hers for as long as they lived. What is more, while the assumption of Richard's guilt depends on a posthumous reputation for savagery it was Henry VII (and later Henry VIII) who would, one by one, eliminate all the rival Yorkist line with chilling efficiency'.

Gristwood certainly had a point, for Henry VII would later order the executions of the nephew of Richard, Edward earl of Warwick, and also had executed Perkin Warbeck, a pretender (but whom, some believe, may actually have been the younger of the two Princes). Henry VIII was similarly ruthless in the 1530s. However, no surviving source material from the time actually suggests that Henry was believed to be the culprit. True, Tudor historians would hardly have dared to have challenged their king and accused him of murder, but no foreign sources written on the Continent connected Henry Tudor with the Princes' murders. Even Margaret of Burgundy, who continually plotted against him, never accused him of her nephews' deaths.

Some actually believed that Henry avenged the princes' deaths. The Crowland Chronicler, for instance, wrote how 'the children of King Edward' had been 'avenged' at Bosworth in 1485 through Henry's victory and Richard's death.

Furthermore, Henry's only real opportunity to murder the two Princes would have been on his accession in 1485, for he had been dwelling in Europe prior to that. By all accounts, however, the two boys were last seen in the autumn of 1483 - almost 2 years previously. It is, admittedly, possible that Henry ordered one of his servants or a loyal supporter to travel to England and commit the deed, but there is no evidence of this.

Others suspect that it was Richard's former supporter, the Duke of Buckingham, who had the Princes murdered. The contemporary Historical notes of a London citizen stated that 'King Edward the Vth, late called Prince of Wales and Richard Duke of York, his brother... were put to death in the Tower of London by the vise [advice] of the Duke of Buckingham' (although this does not actually mean that Buckingham himself killed the princes). The private secretary to the king of Portugal, Alfonso V, recounted how '...after the passing away of king Edward in the year of 83, another one of his brothers, the Duke of Gloucester, had in his power the Prince of Wales and the Duke of York, the young sons of the said king his brother, and turned them to the Duke of Buckingham, under whose custody the said Princes were starved to death'. Yet Buckingham had left the court on progress at Gloucester in early August, travelling to his residence, before leading a rebellion in Wales - there is no evidence that he was in London at the time.

Buckingham had become increasingly disaffected with Richard and had rebelled against him in the autumn of 1483, before being executed on 2 November. However, the rebellion may have been aimed at actually freeing the princes - so why would he then have killed them? But this becomes murkier when one considers that Buckingham himself had royal blood (he had also been the husband of one of Elizabeth Woodville's younger sisters, who he resented). Yet, as Weir notes, Richard never accused Buckingham of murdering his nephews before his execution for treason, which would have been a crime, and which he surely would have done if evidence had come forth suggesting Buckingham was responsible, thus deflecting from the rumours which linked Richard with their deaths. Moreover, The Great Chronicle suggested that rumours of the Princes' deaths did not circulate in London until Easter 1484, which if true, meaning that the Princes were still alive at the end of 1483, removes the possibility of Buckingham's culpability, for he had been executed in November 1483.

Overall, the evidence thus far seems to indicate that the traditional assumption that Richard was the culprit is probably correct. However, some revisionist historians believe that one, or both, of the Princes actually survived. A visitor from Silesia in 1484, Nicolaus von Popplau, recorded: 'many people say - and I agree with them - that they are still alive and kept in a very dark cellar', but of course, they might have been killed shortly afterwards. One might question, furthermore, how Poppau and 'many people' knew specifically that the princes were alive and kept in a cellar. Vergil reported rumours which suggested that they had been exiled to 'some secret land'. Historians such as David Baldwin believe that the younger prince, Richard Duke of York, actually survived, and became a bricklayer in Essex. Yet his evidence has not proved compelling.

Audrey Williamson, author of The Mystery of the Princes, suggested that Elizabeth Woodville left sanctuary because she was promised by Richard that both, or her younger son, would be allowed to join her and live with her. Williamson believes that the younger Prince may have later dwelt at Gipping Hall in Suffolk, along with other royal children. More intriguingly, this was the seat of the Tyrell family, whom Tudor historians believed was responsible for their deaths. But as has been stated, if either, or both of, the princes was sent to Gipping Hall, 'someone would surely have got to know about it... It is likely that several of those who served the Queen could have recognised her sons. Thus it would have been virtually impossible to keep the existence of the Princes a secret, especially in the face of rumours of their deaths'.

Other historians have suggested that one of the pretenders in the reign of Henry VII, Perkin Warbeck, may actually have been the younger prince, Richard. Throughout the 1490s, Warbeck invaded England, hoping to gain support for 'his' crown, supported by many European powers including Margaret of Burgundy, the Scottish king, and King Maximilian I. Margaret personally tutored Warbeck in the ways of the Yorkist court - of course, if this was actually her nephew, it explains her actions; but it is more likely that she knew he was an imposter but supported his venture against her sworn enemy Henry VII. Warbeck was reported to resemble Richard of York in his appearance (although one might question when anyone had last seen Richard alive, especially since he had only been a child of 10, whereas Warbeck was somewhat older). However, Warbeck later confessed to being an imposter, being of Flemish origin. This is somewhat confirmed by the fact that many of the family ties he recounted in his later confession have been backed up by the municipal archives of Tournai.

Certainly, by the autumn of 1483, it is likely that the elder prince was dead. Evidence suggests that he had been gravely ill, possibly suffering osteomyelitis, a bone disease. More seems to suggest that he may have suffered depression. Possibly, then, he died of natural causes, but his murder cannot be ruled out. It is significant that no pretenders ever claimed to be him - instead, it was his younger brother they chose to represent.

The evidence put forward here indicates that it is impossible to be certain what happened. Rumours are often untrustworthy, the evidence is contradictory, and much of it was compiled significantly later, in the age of the Tudors, by those hostile to Richard III and his legacy. However, it seems likely that both Princes died in the Tower by the end of 1483. Theories of one Prince's survival, or indeed both, are not convincing and do not put forward compelling evidence. For me, the most convincing evidence which suggests that both died within the Tower was the discovery of two corpses in 1674, clearly of children, who were about the same age as the Princes would have been. The only problem, of course, is the sex - they were not definitively known to be male. But then, who else could they be?

We will never know for certain just what happened to the Princes. But, taking everything into account, I would still tentatively put Richard as the culprit, believing that both boys were dead by the end of 1483. At least five other monarchs put to death people who they feared would take the succession from them. His own brother, Edward, ordered his brother George's execution. Henry VIII executed 2 of his wives, and several maternal relatives. His two daughters, Mary and Elizabeth, each executed a fellow queen and cousin. I do not think Richard was evil or corrupt, as Shakespeare presents him. But I think that he strongly wanted to be King of England. He was aware of his brother's popularity, and knew that, as long as his 2 nephews lived, they would always have the stronger claims to the throne, and would always be the focus for rebellion and dissent against his regime. Their deaths were necessary, even if he regretted them.

I have just read Alison Weir's ' Elizabeth of York' - and half way through I suddenly thought - Margaret Beaufort murdered the princes in the Tower - of all people she wanted them dead because her son Henry had a very shaky claim and a marriage to Elizabeth would help his claim, but not if the princes were alive and Margaret had plotted to make Henry the king for years and she was married to Stanley who supported Henry at the last minute at Bosworth. I didn't realise until I read this blog that Margaret had been considered as the culprit previously but it was more or less rejected because no-one knows where she was in the summer of 1483 - but she was in touch with Elizabeth Woodville via her priest who visited Woordville in sanctuary - so she could easlly have organised the deaths of the princes if she wanted to.

ReplyDeleteI agree! I think that she convinced Stanley to speak with Richard, to convince him,that the Boys were a major threat to his claim and so then he ordered their murder! Margaret wasn't directly involved but she was a very smart woman who wanted her son on the throne!

ReplyDeleteStanley then of course backed Henry Tudor and Margaret got what she wanted! Her son as king, with no princes to take that away from him!